What happens when you kick millions of teens off social media? Australia’s about to find out

It’s August, and a show of hands in an auditorium filled with 300 students at All Saints Anglican School in Australia shows that few of the Grade 9 and 10 students sitting in plush red seats had heard of the country’s impending ban on social media, much less how to prepare for it. “It’s very important to save photos,” Kirra Pendergast, founder of cyber safety organization Ctrl+Shft, lectures from the stage. “You need to prepare.” An alarmed murmur spreads around the room as the students realize what’s about to be lost. “Can you get your account back when you turn 16?” one girl asks. “What if I lie about my age?” asks another. Less than two weeks before the ban, we have more answers.

In This Article:

- From December 10 social media platforms must prove age limits or face fines

- Meta and Snap announce actions

- Eight weeks of no school, no teachers, and no scrolling

- A summer of silence for millions of children

- Global echoes and the safety belt moment

- Origins and politics of the ban

- Legal challenges and government response

- Global responses and domestic pushback

- Spokespeople push back and government reaffirmation

- Sharing a future with the next generation

- Spokespeople push back and government reaffirmation

- Maxine, Zoey and the movement to rethink age limits

- Queueing up for a different summer

- Different responses and the push for safer spaces

- Personal stories from the classroom

From December 10 social media platforms must prove age limits or face fines

From December 10, sites that meet the Australian government’s definition of an “age-restricted social media platform” will need to show that they’re doing enough to eject or block children under 16 or face fines of up to 49.5 million Australian dollars ($32 million). The list includes Snapchat, Facebook, Instagram, Kick, Reddit, Threads, TikTok, Twitch, X, and YouTube. The government says it’s protecting children from potentially harmful content; the sites say they’re already building safer systems.

Meta and Snap announce actions

Meta says it’ll start deactivating accounts and blocking new Facebook, Instagram and Threads accounts from December 4. Under-16s are being encouraged to download their content. Snap says users can deactivate their accounts for up to three years, or until they turn 16. Snap streaks – the daily swapping of photos of ordinary life, vacations, walls, foreheads, anything to signal an online presence – will end.

Eight weeks of no school, no teachers, and no scrolling

There’s another sting in the ban, too, coming at the end of the Australian school year before the summer break in the southern hemisphere. For eight weeks, there’ll be no school, no teachers – and no scrolling.

A summer of silence for millions of children

For millions of children, it could be the first school break they spend in years without the company of time-killing social media algorithms, or an easy way to contact their friends. Even for parents who support the ban, it could be a very long summer.

Global echoes and the safety belt moment

Other countries around the world are taking notes as Australia explores new territory that some say mirrors safety evolutions of years past – the dawning realization that maybe cars need safety belts, and that perhaps cigarettes should come with some kind of health warning. As with any seismic step in social policy, there are cheer squads, naysayers and those who don’t care what Australia – a country known to love rules – is doing to (and for) its children. But leaders in other countries are closely watching Australia’s eSafety tzar and are crafting their own legislation, so there’s every chance that bans will spread.

Origins and politics of the ban

The origins of the ban are widely attributed to the wife of an Australian state premier who had read “The Anxious Generation” by US psychologist and author Jonathan Haidt and urged her husband to do something about it. In his book, Haidt attributes the rise of mental health issues in children and young adults to the lack of unsupervised outdoor play and the proliferation of smartphones. South Australia launched an inquiry into how a ban might work, before the idea spread nationwide backed by campaigns launched by News Corporation, which dominates Australia’s media landscape, and a Sydney radio presenter who publicized the stories of families who’d lost children to suicide caused by online bullying under a campaign called “36 Months.” The national bill – passed on the final day of parliament last year – was criticized at the time as a rushed piece of legislation conceived to win votes before the 2025 election.

Legal challenges and government response

Just this week, the Digital Freedom Project, a campaign group formed to fight the ban, filed a case in Australia’s High Court arguing that it’s a “blatant attack” on the constitutional rights of young Australians to political speech. The group’s president is a Libertarian Party member of the New South Wales state parliament who has previously lobbied against government health restrictions. Any court hearing will take time. Communications Minister Anika Wells hit back in Federal Parliament Wednesday. “We will not be intimidated by threats. We will not be intimidated by legal challenges. We will not be intimidated by big tech. On behalf of Australian parents, we stand firm.”

Global responses and domestic pushback

Malaysia this week became the latest to join a list that includes Denmark, Norway and countries across the European Union, pushed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. The UK’s Online Safety Act threatens multimillion-dollar fines for companies that fail to take appropriate steps to protect children from harmful content. And at least 20 US states have enacted laws relating to children and social media this year, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, but none as sweeping as an outright ban. Separately, hundreds of individuals, school districts and attorneys general from across the US have filed a complaint against Meta, YouTube, TikTok and Snapchat alleging they deliberately embedded addictive features into their platforms to drive advertising revenue, to the detriment of children’s mental health.

Spokespeople push back and government reaffirmation

Spokespeople for Meta, TikTok, and Snap said the filing paints a misleading picture of their platforms and safety efforts. YouTube has been approached for comment. Pendergast, the Ctrl+Shft chief digital strategist, said action to limit the freedom of big tech companies is long overdue. She’s spoken to thousands of Australian children about social media delay – including those at All Saints Anglican School – and is confident that it will make them safer in 2026. “I think it’ll be very different next year. It will take a minute, but we need to make sure that parents know how to teach their children… (about) what to keep and what not to keep, and start to explore safer spaces for them,” she said. However, Nicky Buckley, head of student engagement and culture for All Saints’ junior school, doesn’t expect to notice much of a change in 2026. “I just don’t think some parents are strong enough to remove it,” she said. Her concerns extend to the gaming sites the government has explicitly said won’t be included in the ban, like Roblox, Discord, and Steam. “It absolutely terrifies me,” she said. “I’ve got children as young as year two online and messaging strangers, and it’s not okay.”

Sharing a future with the next generation

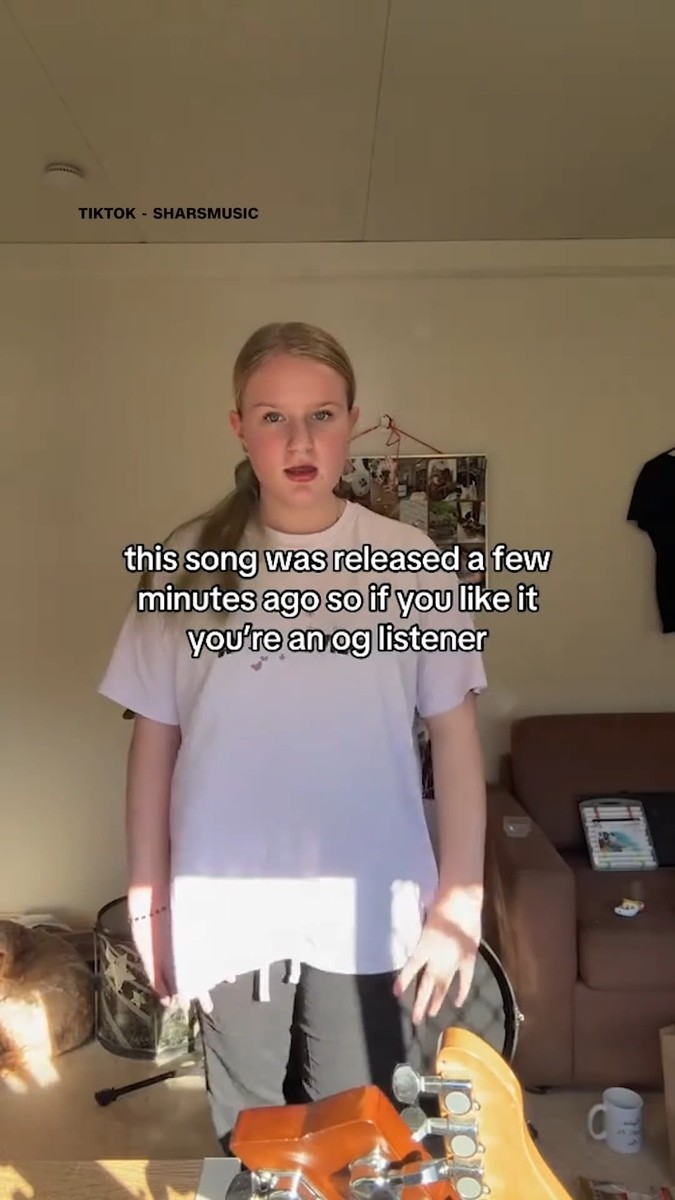

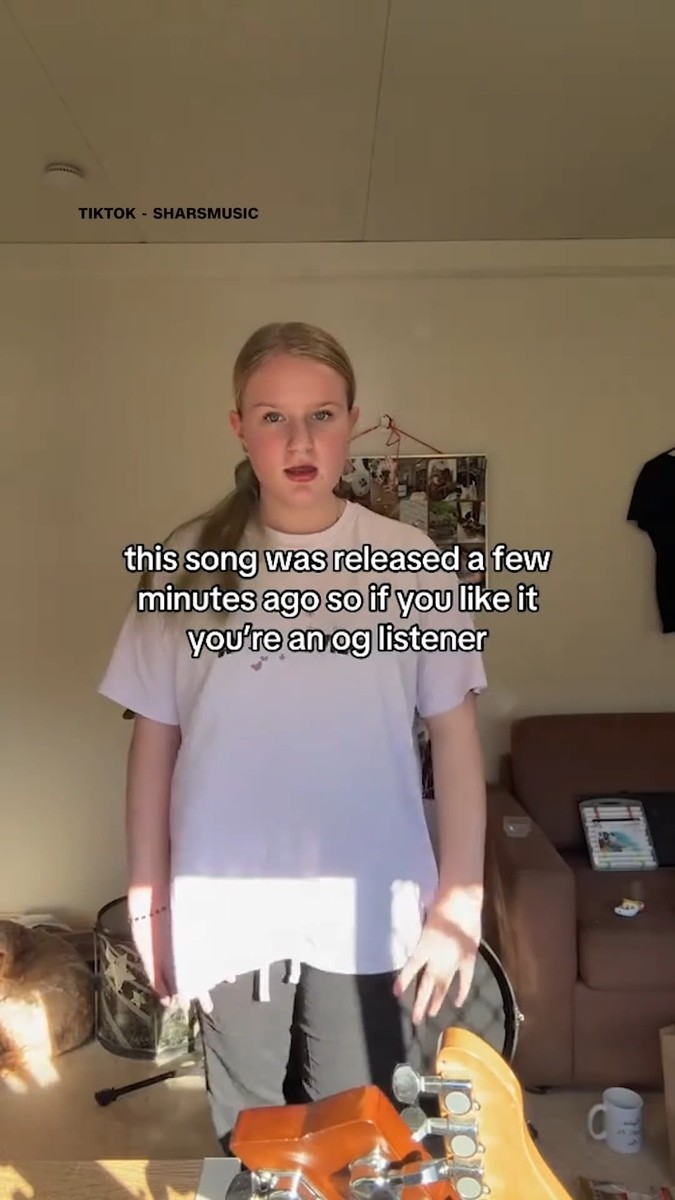

Maxine Steel, a 14-year-old, has her own story about how the ban touches daily life. Shar, a 15-year-old aspiring singer, knows the highs and lows of social media. She was bullied online so badly that she moved schools, but she also relies on social media to promote her music and doesn’t want to lose it. “It took me so long to gain 4,000 followers on my main account from posting, and I’m going to lose all of that,” she said. “Every last person that I’ve gathered to listen to my music – gone.” In just over a year, Shar has grown her music account to around 4,000 followers on TikTok. Like other teen content creators, she’s now urging her followers to move with her to Lemon8, an app owned by TikTok’s parent company ByteDance that hasn’t been banned. Shar’s father, Richie Sharland, says if he had his time again, he would have delayed her access to social media. “I would have left it till she was probably 13 or 14 and had a bit more maturity to handle what was going on. It’s not her, it’s all kids,” he adds. Teen influencer Zoey is also railing against the ban. She uses TikTok to connect with some 48,000 followers, posting #grwm (get ready with me) and unboxing videos, and – more recently – advice for under-16s about how to evade age detection. “Change your email address on your social media accounts to your parent’s email,” advised Zoey, whose own account includes her father’s name. (TikTok says the name of the account doesn’t matter – their technology can detect who’s using it most often). Zoey, 14, started a petition to have the Australian social media ban lowered to age 13. Zoey’s parents support her use of social media and believe it’s been good for her. “What she’s done and how she’s gone about it, it’s amazing. It really is,” Mark, her father, told the “Youth Jam” podcast. Zoey started a petition calling for the age limit on the social media ban to be lowered to 13, which had garnered more than 43,000 signatures by the time it closed on Wednesday. Grade 9 student Maxine Steel didn’t sign it. She deleted her social media apps last year, after finding it too difficult to stop scrolling. Right now, she doesn’t have a phone at all. For the last term of this school year, she’s at a leadership camp in Victoria state’s High Country with 40 or so other 14-year-old students at the Alpine School, where phones are banned. “In the first week … we were all discussing about how we missed everyone, we couldn’t talk to our friends, and we just, like, missed scrolling,” Maxine said during a school-approved call. “Now we’ve really settled in, everyone’s forgotten about social media, and I have to say, it is the most vivid and animated environment I think I’ve ever been in my whole life.” Maxine is a member of Project Rockit’s National Youth Collective – a group of 50 young people across Australia who inform programs combating bullying, hate and prejudice. Project Rockit works in schools and provides safety advice to tech companies including Snapchat, Spotify and Meta’s Facebook and Instagram. Lucy Thomas, Project Rockit’s co-founder and CEO, says while Maxine has found it empowering to log off social media, other kids are feeling genuine grief about losing their connection with support groups and others like them. “Young people’s relationships with these platforms are really complex and diverse, and while some thrive without them, others really do utilize social media as their primary way to stay connected,” said Thomas. The National Youth Collective is currently brainstorming ways to reach out to isolated, marginalized and lonely children. “The last thing we want is for them to pop up on more dangerous, less regulated spaces as a result of a policy that was intended to keep them safer,” said Thomas. It’s worth remembering how we got here. The origins of the ban are widely attributed to the wife of an Australian state premier who had read “The Anxious Generation” by US psychologist and author Jonathan Haidt and urged her husband to do something about it. In his book, Haidt attributes the rise of mental health issues in children and young adults to the lack of unsupervised outdoor play and the proliferation of smartphones. South Australia launched an inquiry into how a ban might work, before the idea spread nationwide backed by campaigns launched by News Corporation, which dominates Australia’s media landscape, and a Sydney radio presenter who publicized the stories of families who’d lost children to suicide caused by online bullying under a campaign called “36 Months.” The national bill – passed on the final day of parliament last year – was criticized at the time as a rushed piece of legislation conceived to win votes before the 2025 election. Just this week, the Digital Freedom Project, a campaign group formed to fight the ban, filed a case in Australia’s High Court arguing that it’s a “blatant attack” on the constitutional rights of young Australians to political speech. The group’s president is a Libertarian Party member of the New South Wales state parliament who has previously lobbied against government health restrictions. Any court hearing will take time. Communications Minister Anika Wells hit back in Federal Parliament Wednesday. “We will not be intimidated by threats. We will not be intimidated by legal challenges. We will not be intimidated by big tech. On behalf of Australian parents, we stand firm.”

Spokespeople push back and government reaffirmation

Spokespeople for Meta, TikTok, and Snap said the filing paints a misleading picture of their platforms and safety efforts. YouTube has been approached for comment. Pendergast, the Ctrl+Shft chief digital strategist, said action to limit the freedom of big tech companies is long overdue. She’s spoken to thousands of Australian children about social media delay – including those at All Saints Anglican School – and is confident that it will make them safer in 2026. “I think it’ll be very different next year. It will take a minute, but we need to make sure that parents know how to teach their children… (about) what to keep and what not to keep, and start to explore safer spaces for them,” she said. However, Nicky Buckley, head of student engagement and culture for All Saints’ junior school, doesn’t expect to notice much of a change in 2026. “I just don’t think some parents are strong enough to remove it,” she said. Her concerns extend to the gaming sites the government has explicitly said won’t be included in the ban, like Roblox, Discord, and Steam. “It absolutely terrifies me,” she said. “I’ve got children as young as year two online and messaging strangers, and it’s not okay.”

Maxine, Zoey and the movement to rethink age limits

Shar, a 15-year-old aspiring singer, knows the highs and lows of social media. She was bullied online so badly that she moved schools, but she also relies on social media to promote her music and doesn’t want to lose it. “It took me so long to gain 4,000 followers on my main account from posting, and I’m going to lose all of that,” she said. “Every last person that I’ve gathered to listen to my music – gone.” In just over a year, Shar has grown her music account to around 4,000 followers on TikTok. Like other teen content creators, she’s now urging her followers to move with her to Lemon8, an app owned by TikTok’s parent company ByteDance that hasn’t been banned. Shar’s father, Richie Sharland, says if he had his time again, he would have delayed her access to social media. “I would have left it till she was probably 13 or 14 and had a bit more maturity to handle what was going on. It’s not her, it’s all kids,” he adds. Teen influencer Zoey is also railing against the ban. She uses TikTok to connect with some 48,000 followers, posting #grwm (get ready with me) and unboxing videos, and – more recently – advice for under-16s about how to evade age detection. “Change your email address on your social media accounts to your parent’s email,” advised Zoey, whose own account includes her father’s name. (TikTok says the name of the account doesn’t matter – their technology can detect who’s using it most often). Zoey, 14, started a petition to have the Australian social media ban lowered to age 13. Zoey’s parents support her use of social media and believe it’s been good for her. “What she’s done and how she’s gone about it, it’s amazing. It really is,” Mark, her father, told the “Youth Jam” podcast. Zoey started a petition calling for the age limit on the social media ban to be lowered to 13, which had garnered more than 43,000 signatures by the time it closed on Wednesday. Grade 9 student Maxine Steel didn’t sign it. She deleted her social media apps last year, after finding it too difficult to stop scrolling. Right now, she doesn’t have a phone at all. For the last term of this school year, she’s at a leadership camp in Victoria state’s High Country with 40 or so other 14-year-old students at the Alpine School, where phones are banned. “In the first week … we were all discussing about how we missed everyone, we couldn’t talk to our friends, and we just, like, missed scrolling,” Maxine said during a school-approved call. “Now we’ve really settled in, everyone’s forgotten about social media, and I have to say, it is the most vivid and animated environment I think I’ve ever been in my whole life.” Maxine is a member of Project Rockit’s National Youth Collective – a group of 50 young people across Australia who inform programs combating bullying, hate and prejudice. Project Rockit works in schools and provides safety advice to tech companies including Snapchat, Spotify and Meta’s Facebook and Instagram. Lucy Thomas, Project Rockit’s co-founder and CEO, says while Maxine has found it empowering to log off social media, other kids are feeling genuine grief about losing their connection with support groups and others like them. “Young people’s relationships with these platforms are really complex and diverse, and while some thrive without them, others really do utilize social media as their primary way to stay connected,” said Thomas. The National Youth Collective is currently brainstorming ways to reach out to isolated, marginalized and lonely children. “The last thing we want is for them to pop up on more dangerous, less regulated spaces as a result of a policy that was intended to keep them safer,” said Thomas. It’s worth remembering how we got here. The origins of the ban are widely attributed to the wife of an Australian state premier who had read “The Anxious Generation” by US psychologist and author Jonathan Haidt and urged her husband to do something about it. In his book, Haidt attributes the rise of mental health issues in children and young adults to the lack of unsupervised outdoor play and the proliferation of smartphones. South Australia launched an inquiry into how a ban might work, before the idea spread nationwide backed by campaigns launched by News Corporation, which dominates Australia’s media landscape, and a Sydney radio presenter who publicized the stories of families who’d lost children to suicide caused by online bullying under a campaign called “36 Months.” The national bill – passed on the final day of parliament last year – was criticized at the time as a rushed piece of legislation conceived to win votes before the 2025 election. Just this week, the Digital Freedom Project, a campaign group formed to fight the ban, filed a case in Australia’s High Court arguing that it’s a “blatant attack” on the constitutional rights of young Australians to political speech. The group’s president is a Libertarian Party member of the New South Wales state parliament who has previously lobbied against government health restrictions. Any court hearing will take time. Communications Minister Anika Wells hit back in Federal Parliament Wednesday. “We will not be intimidated by threats. We will not be intimidated by legal challenges. We will not be intimidated by big tech. On behalf of Australian parents, we stand firm.”

Queueing up for a different summer

Other countries are proposing their own restrictions. Malaysia this week became the latest to join a list that includes Denmark, Norway and countries across the European Union, pushed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. The UK’s Online Safety Act threatens multimillion-dollar fines for companies that fail to take appropriate steps to protect children from harmful content. And at least 20 US states have enacted laws relating to children and social media this year, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, but none as sweeping as an outright ban. Separately, hundreds of individuals, school districts and attorneys general from across the US have filed a complaint against Meta, YouTube, TikTok and Snapchat alleging they deliberately embedded addictive features into their platforms to drive advertising revenue, to the detriment of children’s mental health. Spokespeople for Meta, TikTok, and Snap said the filing paints a misleading picture of their platforms and safety efforts. YouTube has been approached for comment.

Different responses and the push for safer spaces

Pendergast, the Ctrl+Shft chief digital strategist, said action to limit the freedom of big tech companies is long overdue. She’s spoken to thousands of Australian children about social media delay – including those at All Saints Anglican School – and is confident that it will make them safer in 2026. “I think it’ll be very different next year. It will take a minute, but we need to make sure that parents know how to teach their children… (about) what to keep and what not to keep, and start to explore safer spaces for them,” she said. However, Nicky Buckley, head of student engagement and culture for All Saints’ junior school, doesn’t expect to notice much of a change in 2026. “I just don’t think some parents are strong enough to remove it,” she said. Her concerns extend to the gaming sites the government has explicitly said won’t be included in the ban, like Roblox, Discord, and Steam. “It absolutely terrifies me,” she said. “I’ve got children as young as year two online and messaging strangers, and it’s not okay.”

Personal stories from the classroom

Maxine, the 14-year-old who removed herself from social media, reflects on the coming year. “If you’re about my age, you’ll have it back next year anyway, so why not have 365 days of peace and silence, where you just focus on yourself and try to enjoy your last years of childhood before you start growing up.”