Ultra-rich pay up to $10,000 to filter microplastics from their blood in a bid for longevity

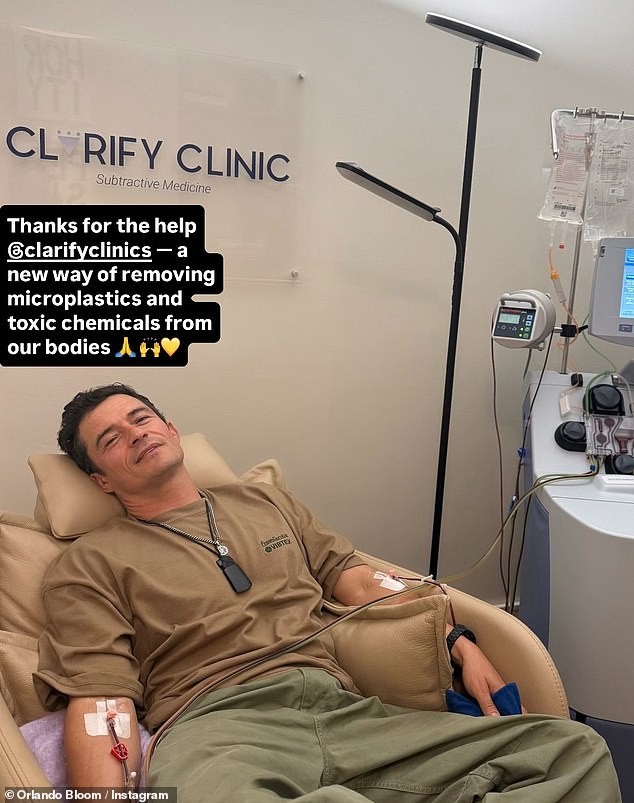

From oxygen chambers to stem-cell infusions and full-body MRIs, the ultra-rich have chased longevity for years. Now a new trend has emerged: paying up to $10,000 per session to filter microplastics and other toxins from their blood. In the last six months, Orlando Bloom, former Dallas Cowboys quarterback Troy Aikman and Star Trek actor Paul Wesley have all posted snaps of themselves having the procedure. In October last year, biohacking mogul Bryan Johnson revealed he had tried the treatment, after previously swapping his plasma with that of his then 17-year-old son.

In This Article:

- What plasmapharesis really is and how it is supposed to work

- Celebrities join the trend and share their experiences

- Perceived effects and early results are mixed

- Costs, clinics and the price tag of a health fad

- Experts warn against over-claiming benefits and scrutinize microplastics claims

- A medical context: where plasmapharesis fits in medicine

What plasmapharesis really is and how it is supposed to work

In the procedure, known as plasmapharesis or therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), patients are hooked up to a machine that filters plasma out of their blood and replaces it with albumin, the most abundant protein in the blood. Blood plasma can contain inflammation-causing proteins, microplastics, forever chemicals and other potentially harmful substances. The albumin replaced the plasma and does not contain these toxins.

Celebrities join the trend and share their experiences

In the last six months, Orlando Bloom, Troy Aikman and Paul Wesley have all posted snaps of themselves undergoing the procedure, signaling how far the trend has spread among the social and celebrity biohacking scene. After removing plasma, patients claim they feel different in profound ways: “After removing the plasma in the procedure, patients claim it has left them feeling 'incredible' and 'more relaxed'.” Clarify Clinics offers a similar method to TPE, costing $12,700, but its approach filters the patient’s own plasma of toxins before returning it. Bryan Johnson, 48, said he underwent TPE to ‘remove toxins from my body’, and wrote on X after the procedure: ‘The operator, who’s been doing TPE for nine years, said my plasma is the cleanest he’s ever seen. By far. He couldn’t get over it.’ TPE takes around two to three hours to complete and requires patients to sit in a chair with an IV in both arms. During the procedure, the machine removes about 75 percent of plasma, about two out of the 2.7 liters of plasma an adult is estimated to have. Overall, adults have between 4.7 and 5.7 liters of total blood in their bodies.

Perceived effects and early results are mixed

After the procedure, doctors say effects appear over the days afterward, with claims of potential benefits for longevity, immune function and cell health. Johnson admitted that it had little effect: in an Instagram video, he said: 'So, what happened [to me] when you removed the plasma from your body? Nothing really. I felt the same, went to bed, slept the same. So, for me, it was pretty inconsequential.'

Costs, clinics and the price tag of a health fad

Patients are encouraged to get the procedure twice yearly, leading to a total annual cost of around $20,000. Dr Keith Smigiel, an Arizona-based doctor who offers the procedure, told the New York Post that patients say the sensation after the procedure is equivalent to a 'cross-country flight' with a 'jet lag' sensation at the end. Clarify Clinics offers a similar option at $12,700.

Experts warn against over-claiming benefits and scrutinize microplastics claims

California-based health researchers Rosa Busquets, a forensic chemist at Kingston University, and Luiza Campos, an environmental engineering expert at University College London, wrote on The Conversation that TPE is similar to dialysis, a life-saving treatment for kidney failure where waste is filtered from the blood. They explained: 'Dialysis filters waste products like urea and creatinine from the blood, regulates electrolytes, removes excess fluid and helps maintain blood pressure.' They cautioned that claims TPE could filter microplastics or other toxic compounds are unproven and urged skepticism: 'It's tempting to believe, as Bloom seems to, that we can simply "clean" the blood, like draining pasta or purifying drinking water.' They added: 'Currently, there is no published scientific evidence that microplastics can be effectively filtered from human blood. So, claims that dialysis or other treatments can remove them should be viewed with skepticism, especially when the filtration systems themselves are made from plastic.' Finally, they warned: 'While it's tempting to chase quick fixes or celebrity-endorsed cleanses, we are still in the early stages of understanding what microplastics are doing to our bodies, and how to get rid of them.'

A medical context: where plasmapharesis fits in medicine

Therapeutic plasma exchange has historically been used to treat certain autoimmune conditions by removing antibodies that trigger immune system attacks. In the US, there are an estimated 17,000 TPE procedures carried out in hospitals each year, though these are for sick patients; it is not clear how many people pay out of pocket for the treatment.