The Sacred Pharmacy of the Maya: How Hallucinogenic Substances Shaped a Civilization

From roughly 2000 BCE to 1500 CE, the Maya built a civilization in which the natural world and the spiritual realm were deeply connected. In their rituals, mind-altering plants were sacred tools—vehicles for speaking with the gods, gaining hidden knowledge, and guiding the community. Among the most notable substances was peyote, a small spineless cactus that contains mescaline. The Maya used it in ceremonies to reach the spirit world, often within a larger ceremonial context that included chanting, music, and dance. Shamanic leaders guided these journeys, acting as intermediaries between the human and the divine.

In This Article:

A World Beyond Sight: The Maya’s Sacred Drug Use

Peyote rituals were an integral part of Maya religious life. The substances were considered sacred and used to communicate with the divine, seek guidance, and undergo transformative experiences. Peyote was typically consumed as a beverage or dried and chewed, and its use occurred within ceremonies that featured chanting, music, and dance. The rituals served not only spiritual aims but also the well-being of the community, fostering harmony with the natural world.

Peyote: The Sacred Mescaline Rite

Peyote was a sacred plant in Maya religion, used to contact the spirit world and seek divine guidance. Shamans or religious leaders acted as intermediaries, guiding individuals through the experiences and helping interpret messages. Rituals took place in temples or ceremonial centers, designed to maintain cosmic harmony, foster healing, and support communal well-being. The effects of mescaline—altered consciousness, vivid visions, and a sense of connection to the divine—were understood as gateways to deeper truths.

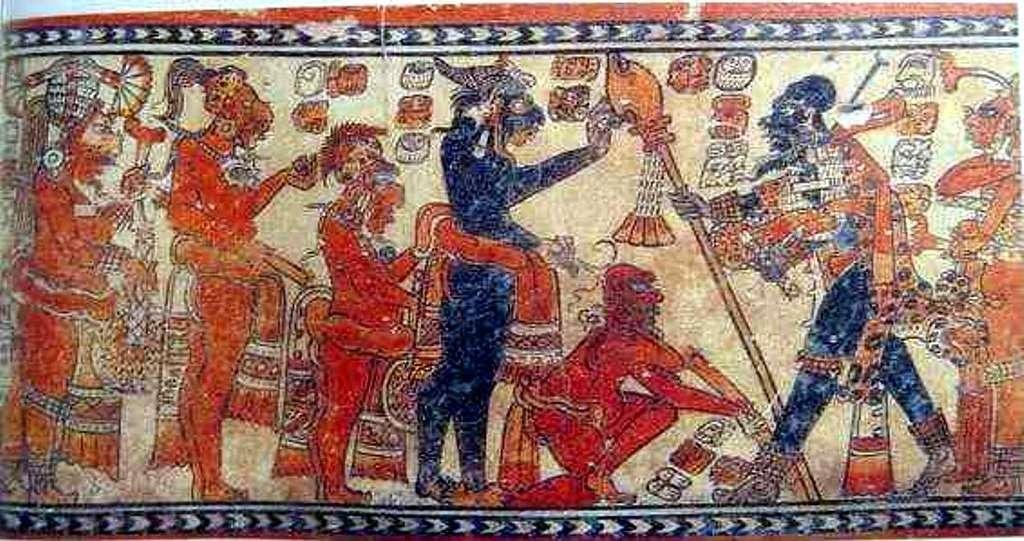

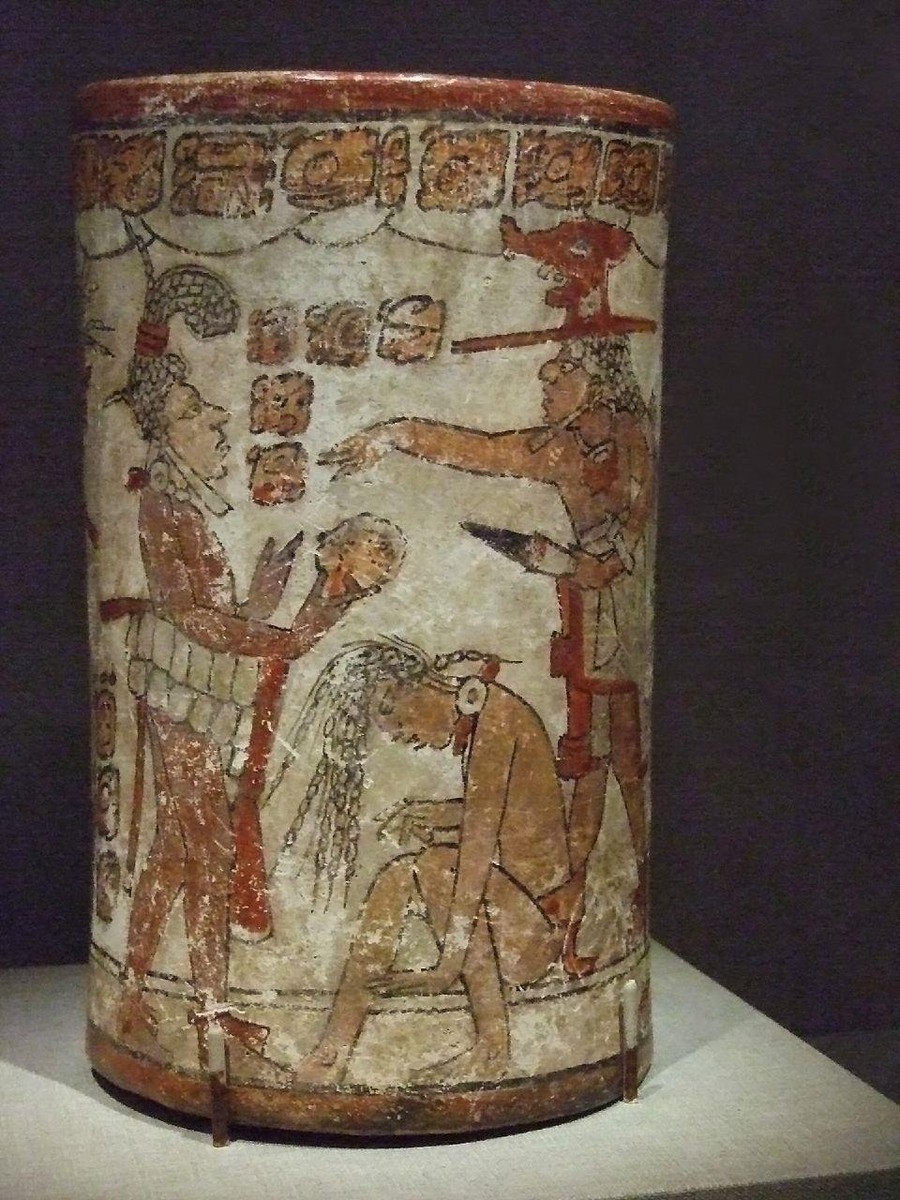

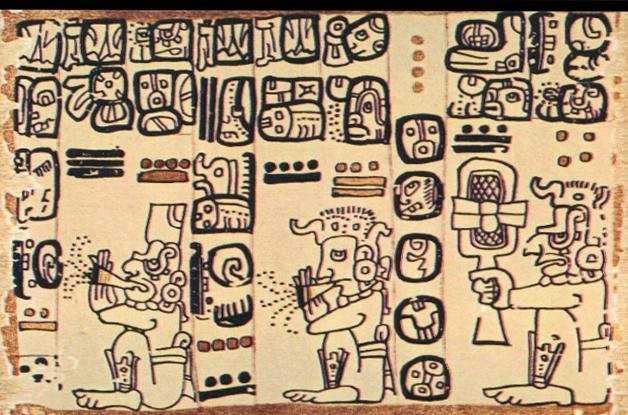

Beyond Peyote: Tobacco, Morning Glory, Jimsonweed, and the Mushroom Question

Tobacco was sacred to the Maya and used for its psychoactive effects and as an offering to the gods. Smoke from pipes or rolled cigars was believed to purify the space and open communication with the spiritual realm. Morning glory seeds (Ipomoea spp.) contain lysergic acid amide, while jimsonweed seeds (Datura spp.) are potent deliriants, used in rituals and healing practices. The question of hallucinogenic mushrooms in Maya culture remains debated. Some scholars hypothesize that certain species of psilocybin mushrooms may have been used, but concrete evidence is limited. Maya art, especially murals and pottery, sometimes depicts mushroom-shaped objects linked to deities or ceremonial scenes. Mushroom rituals are more clearly attested among Zapotecs and Mixtecs, offering broader context for understanding potential Maya practices.

Balché, Incense, and Purification: The Ritual Toolkit

Balché, a fermented drink from balché bark, was consumed during religious festivals and social gatherings to facilitate contact with the spiritual realm. Alongside balché, other fermented beverages—fruit juices and honey wines—also accompanied rituals, strengthening social bonds. Copal resin was burned as incense to purify the ceremonial space and carry prayers to the gods. Enemas were used for healing and spiritual cleansing, administered by healers or priests with specialized tools; these rites prepared the body for sacred experiences and ensured cosmic harmony. Rituals followed precise protocols in elaborately decorated temples or sacred spaces, with shamans guiding participants through each step to maintain the well-being of the community.