The Turkana: A Desert Diet That Could Make You Sick — Meat, Milk, and Blood

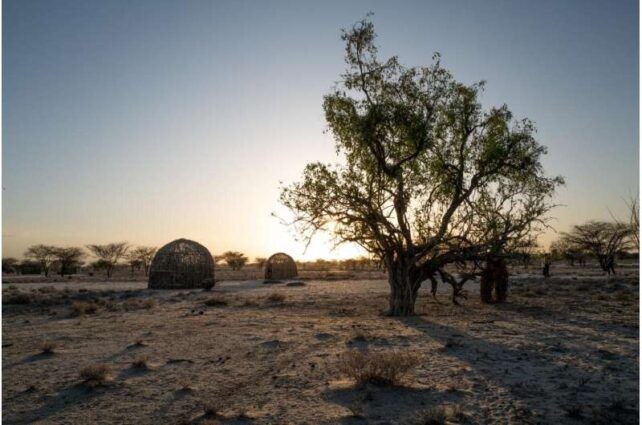

In Northwest Kenya, the Turkana survive in one of the world's harshest deserts by living off their herds—milk, meat, and even blood. Up to 80 percent of their diet comes from animal products. That heavy, meat-centered intake would make most people ill, but generations of Turkana have adapted. Researchers studied 308 Turkana individuals, analyzing nearly eight million gene variants to map the genetic basis of this resilience.

In This Article:

Eight genetic differences that help the Turkana endure dehydration and high-protein life

Among nearly eight million gene variants analyzed across 308 Turkana and comparison groups, researchers identified eight regions where the genomes differ consistently. One notable variant lies in the STC1 gene, which causes the kidneys to retain more water. Lea and colleagues suspect this helps protect the kidneys from the waste products—purines—produced by a meat-heavy diet. Gout is not common among the Turkana.

Evolutionary mismatch: Why urban life can turn advantage into risk

Some Turkana pastoralists still roam, while others have settled in towns or cities. An astonishing majority of pastoralists were chronically dehydrated but otherwise healthy. Researchers warn that these genetic differences could be maladaptive in a city environment, illustrating evolutionary mismatch—the idea that traits once advantageous in past ecologies may harm in new settings. "Evolutionary mismatch occurs when previously advantageous variants, selected for in past ecologies, are placed in novel environments where they instead have detrimental effects," the researchers explain.

What this means for health as the Turkana urbanize

The researchers hope to translate these findings into health programs for the Turkana and other indigenous peoples facing urbanization and environmental changes. "Understanding these adaptations will guide health programs for the Turkana—especially as some shift from traditional pastoralism to city life. It can help doctors anticipate health risks, like kidney strain or metabolic diseases, and design better prevention strategies," said Kenya Medical Research Institute biochemist Charles Miano. This study was published in Science. Some Turkana have shifted from traditional pastoralism to city life while others remain nomadic, highlighting the ongoing challenge of balancing heritage with change.