The stomach talks to the brain: a shocking link between gut rhythms and mental health

For generations, science treated the heart and breathing as the main clues to mood. The gut mattered, too, but the stomach itself was a blank spot in psychiatry. Now a Danish-led study of 243 volunteers shows that the stomach's slow rhythms synchronize with brain activity even at rest. The tighter the stomach-brain link, the higher the levels of anxiety, depression, and stress. Published in Nature Mental Health, this work offers the first objective physiological marker of mental state based on a direct stomach-brain connection.

In This Article:

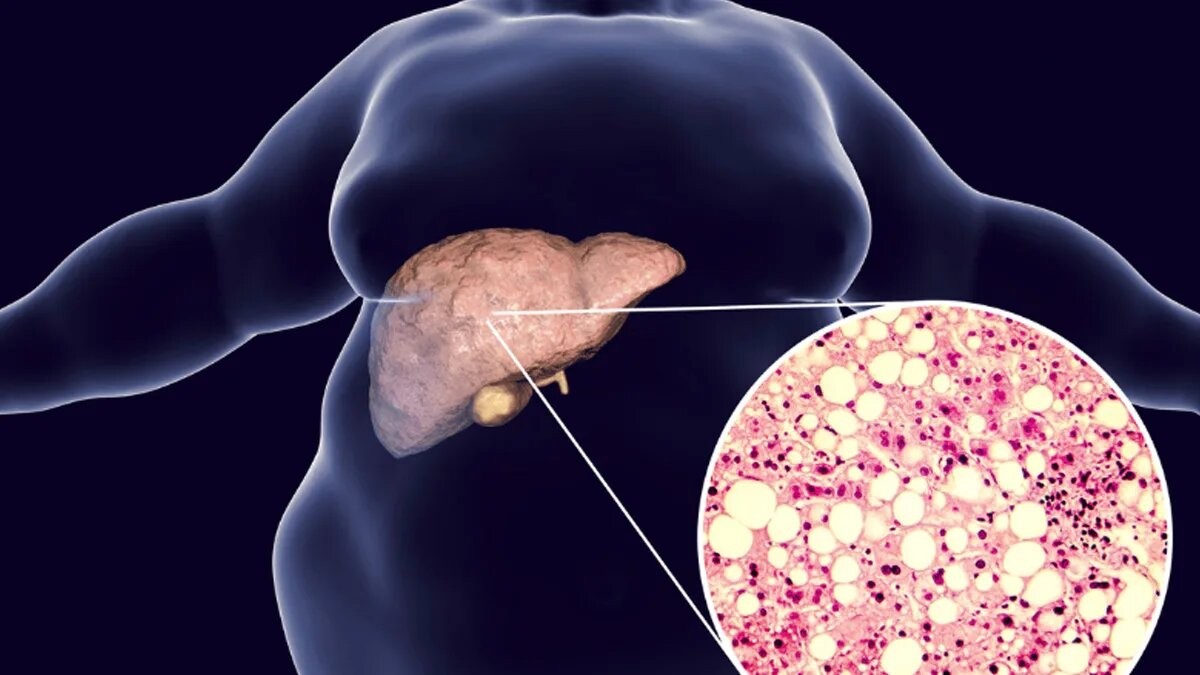

From gut to mind: why the stomach deserves a place in mental health

Until recently, researchers focused on the heart and the gut microbiome; the stomach, the upper gastrointestinal tract, remained a mystery in mental-health research. People have long described fear or disgust as a sensation in the stomach. This study shows those sensations correspond to measurable brain signals, linking gut feelings to brain activity. The finding reframes emotions as something that lives in the stomach as well as in the brain, reminding us that mind and body are deeply connected.

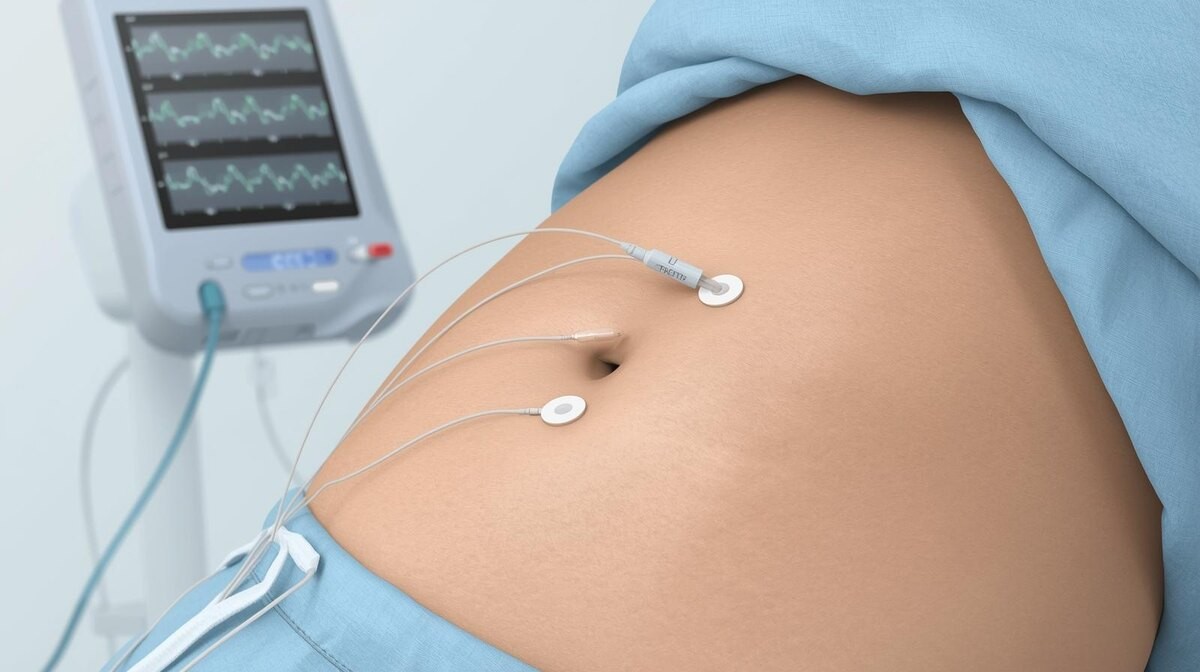

How the study was done

243 volunteers participated in the study. They underwent electrogastrography (EGG) to record stomach electrical activity and resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) to map brain activity. Researchers then compared these data with detailed mental-health questionnaires to see how gut-brain coupling related to anxiety, depression, stress, and fatigue.

What they found: stomach-brain synchrony tracks mental health

The more synchronized the slow rhythms of the stomach were with neural activity in frontoparietal regions, the higher the reported anxiety, depression, and stress. Stronger links appeared in several left and right parietal/frontal areas, and across large-scale networks including the dorsal attention network, the frontoparietal control network, and the ventral attention network. Conversely, healthier mental states were associated with weaker stomach-brain coupling. The model also showed predictive power in an independent sample.

Implications, limits, and a path forward

Researchers propose that mental disorders may involve altered interoception—the brain's sense of the body's signals—causing the stomach to amplify feelings of anxiety and stress. In the future, non-invasive approaches to tune the stomach's rhythm (for example via vagus nerve stimulation or targeted medications) could help recalibrate brain–body communication. However, the study does not establish causation, and the sample size was limited. It nonetheless reshapes our view of mental illness as a body-wide phenomenon and points to new targets for therapy.