Newly discovered galaxy cluster could rewrite our understanding of the universe as it burns five times hotter than expected

A newly discovered galaxy cluster could rewrite our understanding of the cosmos, as scientists spot 'something the universe wasn’t supposed to have'. Researchers found that the cluster was burning five times hotter than expected just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang. Astronomers had thought that such extreme temperatures would only be possible in more mature, stable galaxy clusters that formed later in the universe's life. This hot 'baby cluster' could suggest that the earliest moments of the universe were far more explosive than previously thought. Scientists believe that the unexpected heat might be the product of three supermassive black holes hidden in the depths of the cluster. Using data from a group of telescopes known as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), researchers looked back 12 billion years to study the cluster known as SPT2349-56, which was already enormous for its age. The discovery was published in Nature and relied on ALMA to reveal a newborn cluster that challenges existing ideas about how the intracluster medium heats up.

Unprecedented heat in an immature cluster challenges early-universe models measured by ALMA

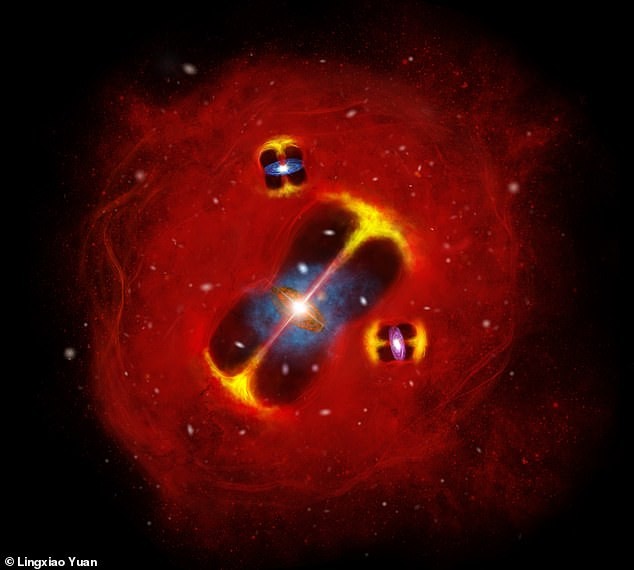

Using the ALMA observatory, scientists measured the temperature of the intracluster medium in a galaxy cluster over 12 billion light-years from Earth and found it far hotter than models predicted for that era. The cluster, dubbed SPT2349-56, was extremely immature yet already extraordinarily large for its age. Its core extends more than 500,000 light-years across, roughly the size of the Milky Way’s halo (about 153,000 parsecs, or ~153 kiloparsecs), and the cluster contains more than 30 extremely active galaxies that form stars over 5,000 times faster than our own Milky Way. However, the measurements show the intracluster medium was far hotter than the models predicted for this time in the universe. Co-author Professor Scott Chapman of Dalhousie University, who conducted the research while at the National Research Council of Canada, says that these black holes were 'already pumping huge amounts of energy into the surroundings and shaping the young cluster, much earlier and more strongly than we thought.' This work comes as astronomers are finding more supermassive black holes in the early universe that appear to have grown much faster than expected.

Why this matters faster black holes in the early universe could rewrite cosmic history

Last year, researchers using the James Webb Space Telescope spotted a 'little red dot' supermassive black hole that was actively growing inside a galaxy just 570 million years after the Big Bang. Importantly, this black hole was much bigger than the size of the host galaxy would suggest. This implies that black holes may have grown faster than the galaxies that hosted them in the early universe, even in relatively small galaxies. Professor Chapman says that studying how these dynamics unfold is critical to explaining the universe around us today. He adds that 'Understanding galaxy clusters is the key to understanding the biggest galaxies in the universe. These massive galaxies mostly reside in clusters, and their evolution is heavily shaped by the very strong environment of the clusters as they form, including the intracluster medium.' Black holes are incredibly dense objects whose gravity is so strong that not even light can escape; they hoover up dust and gas around them, shaping the stars that orbit galaxies. The origins of these giants are still debated, with seeds thought to form either from giant gas clouds hundreds of thousands of times the Sun’s mass or from the collapse of massive stars that end their lives in supernova explosions.