Never Speak to the World of the Dead: Wolf Messing — the man who saw more than others

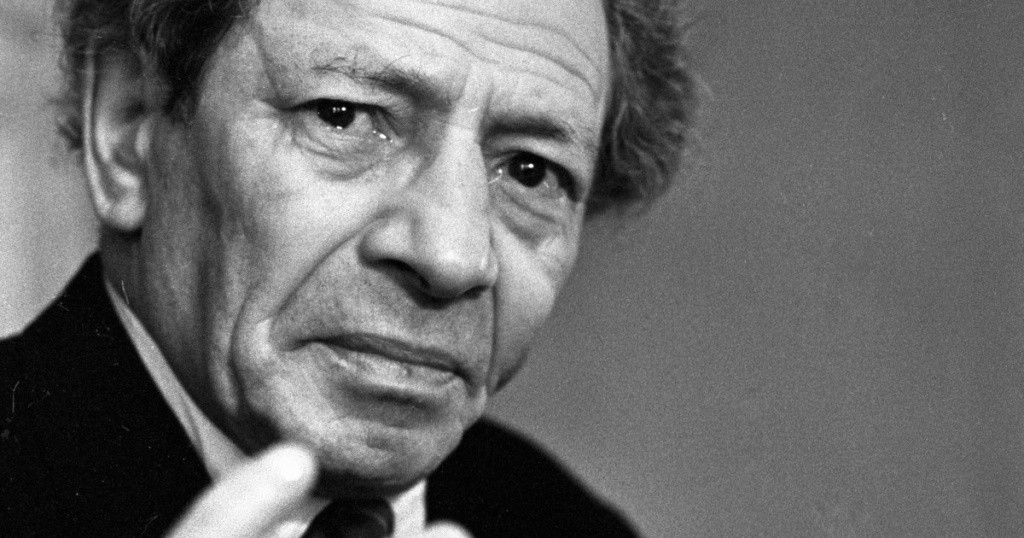

Wolf Messing did more than read minds. He coaxed people to reveal themselves, turning inner fears, hopes, and memories into something almost tangible. Not a magician, but a patient observer, a keen listener, and a reader of souls who understood people to their deepest levels. He was said to predict events, sense fear, and feel joy in others’ hearts. His power lay in extraordinary observation and empathy, not in tricks. To many, he was a man who changed the world around him simply by seeing more.

In This Article:

A gift that reads souls: not magic, but human insight

People from politics, science, and the military sought him out. Some came for spectacle; others for proof; many for comfort in moments of life and death. The gift was not flashy magic but a rare clarity: he could help people open up as easily as turning a page. He could calm an entire hall with a single look. Behind the talent lay a quiet, humane approach: he listened, watched, and sought what lay beneath the surface, then used that understanding to touch others.

Boundaries and warnings: doors you can open only briefly

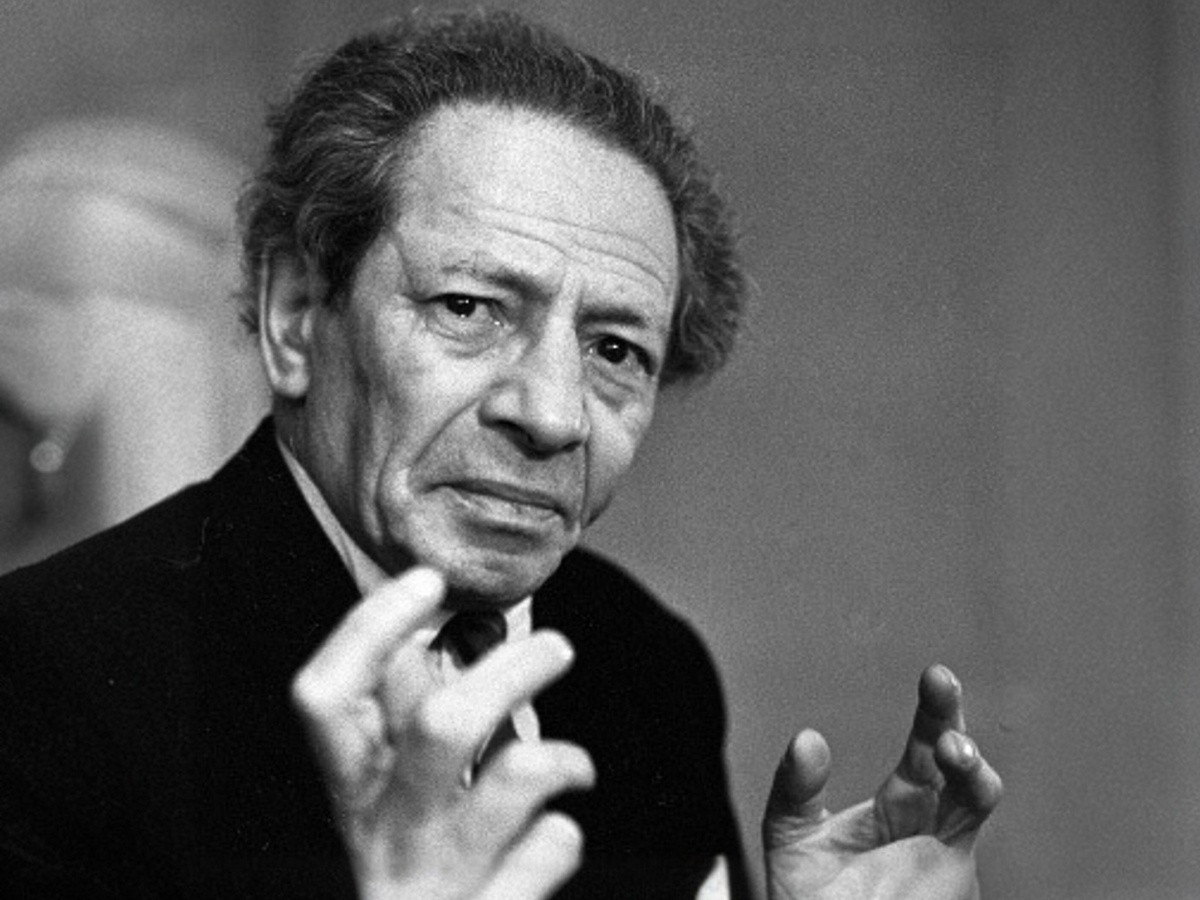

Messing never posed as a fearless intermediary between worlds. He warned that some doors should not be opened — doors you can only nudge ajar for a moment, at a price too high to pay. He spoke plainly, and his cadence often felt like a prayer: care, fear, and the hard wisdom of a life lived close to the edge.

A hall, a question, and a village grave: the living meeting the dead

The most famous moment came when a man asked aloud, 'Where are my parents right now?' The hall fell silent. Messing looked up, pointed to a specific row, described a woman there, and named the father who had died in the war. The match between his words and reality left the audience stunned. Afterward, Messing invited the man to speak privately. The man later said he heard his father’s voice urging him to locate a real village grave—the one with the family name on the stone. The mystery remains unsolved to this day. Messing’s foretelling extended to his own circle: he knew the date his wife Aida would die, and the date of his own death. In the summer of 1960, he argued with the doctor treating Aida, who claimed ten years. Messing shook his head, and the outcome followed his belief.

Final night, a last letter and a philosophy of endings

Death did not scare him, but losing the taste of life frightened him. Before a critical operation for vascular problems, he chose solitude. He moved from room to room, stopped at the window, and then felt a light touch on his head—like a mother stroking a child. A voice spoke: 'That’s it, my dear. You did everything you could. We are proud of you.' After the moment, the spark in his eyes seemed to dim. The operation succeeded, but soon afterward his kidneys failed. In his bed he wrote a final letter: 'Today I will die. I will not suffer. I will wait for the end.' He sent a greeting to Aida: 'She simply left. I will leave soon.' He did not fear death, but he feared losing the taste of life. He believed reincarnation happens rarely, only if the soul has not yet completed its task; otherwise the thread remains unbroken. The mystery endures: he saw what others could not, and his life invites reflection on loss, belief, and the boundaries we avoid.