Myślisz, że znasz Hansa Christiana Andersena? Czterech ekspertów wybrało jego najdziwniejsze baśnie na te święta

Hans Christian Andersen to jeden z najwyżej cenionych duńskich pisarzy — mistrz literackiej baśni, którego wpływ wykracza poza Małą syrenkę, Nowe szaty cesarza i inne klasyki, które wielu z nas poznaje w dzieciństwie. Urodzony w 1805 roku w Odensie na wyspie Funen, Andersen był synem szewca i analfabetycznej pralniarki, który stał się autorem piszącym w różnych gatunkach — powieści, podróże, wiersze i sztuki. Lecz w swoich krótkich opowiadaniach stworzył formę zupełnie swoją własną: emocjonalnie odważną, stylistycznie wynalazczą i bogatą w zarówne czar i egzystencjalny posmak. Chociaż nie wszystkie jego historie dotyczą zimy ani Bożego Narodzenia, Andersen stał się imieniem ściśle kojarzonym z okresem świątecznym na całym świecie. Jego baśnie czytano na głos przez pokolenia, adaptowano do niezliczonych zimowych występów i filmów i wracają co roku dzięki ich mieszance cudowności, melancholii i moralnej wyobraźni. Przypominają, że sezon to nie tylko błysk i świętowanie, ale także refleksja, nadzieja i drobne, kruche cuda bycia człowiekiem. Gdy dni stają się coraz krótsze, poprosiliśmy czterech wiodących ekspertów od Andersena o wybranie jednej baśni, którą ich zdaniem warto czytać — lub ponownie czytać — w te Święta. Ich wybory mogą nie być baśniami, z którymi kojarzy się artysta, ale ukazują autora w jego najgłębszym i najbardziej zabawnym obliczu — i otwierają nowe drogi do jego pisarstwa. Artykuł został zlecony w ramach partnerstwa między Videnskab.dk a The Conversation.

In This Article:

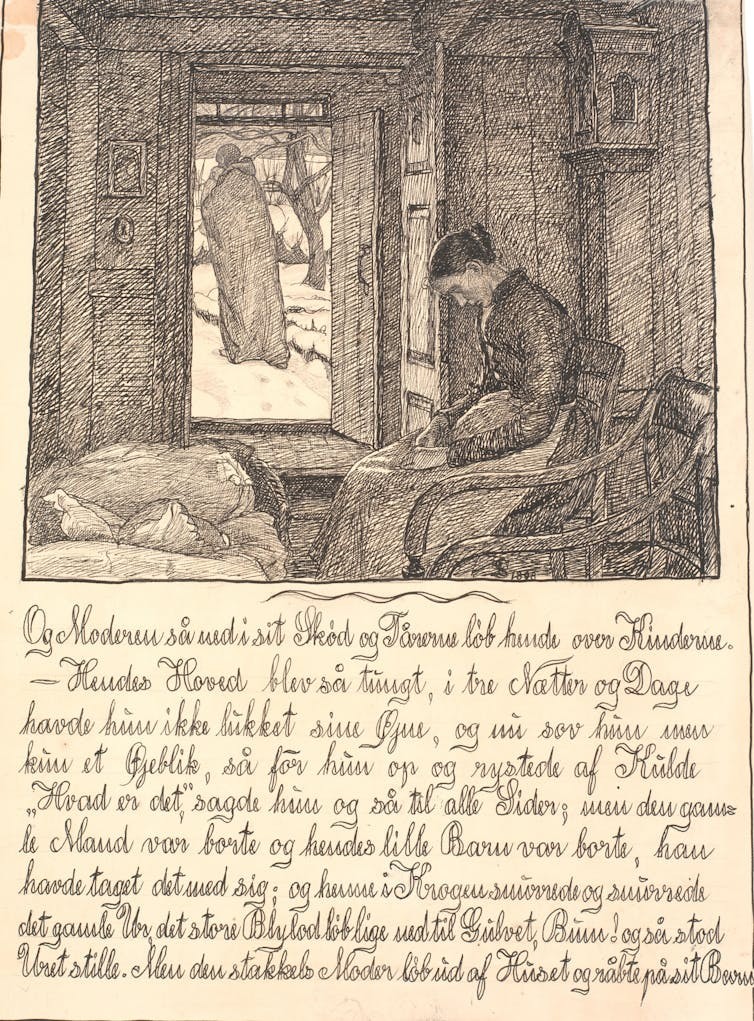

Opowieść matki — matczyna odwaga i cena, jaką płaci człowiek

Ane Grum-Schwensen, associate professor in the Department of Cultural and Linguistic Studies at The Hans Christian Andersen Centre, University of Southern Denmark Wybieranie jednej baśni Andersena jako ulubionej jest prawie niemożliwe. Istnieje tak wiele niezwykłych opowieści, że moja ulubiona często okazuje się ta, którą najczęściej ostatnio odwiedzam. Jednak niektóre historie powracają do mnie wielokrotnie — zarówno w myślach, jak i w badaniach. Jedną z nich jest The Story of a Mother, first published in 1847. It is a fantastic tale in every sense of the word. It includes classic fairy-tale elements: a protagonist – the mother – leaving home and facing trials, helpers guiding her and an ultimate antagonist, Death. Yet Andersen challenges this structure: the helpers demand steep prices and the antagonist could even be seen as a kind of helper. The story also reflects the fantastic, as seen in modern fiction, through its dreamlike quality and its unsettling open ending, where the mother finally allows Death to carry her child into the unknown. This story is profoundly moving. It portrays both the desperate lengths a parent will go to to protect a child and the crushing surrender when confronted with an irreversible fate. Andersen’s ability to capture this parental anguish so vividly, despite never having been a parent himself, is striking. The theme of the dying child was common in 19th-century art and literature, partly because of the harsh reality of child mortality. In the early decades of the century, roughly one-third of all Danish children died before their tenth birthday. Andersen addressed this theme repeatedly. Indeed, his first known poem, at age 11 was written to comfort a grieving mother. Later, in 1827, another poem he wrote, The Dying Child was published anonymously and widely translated. The language and narration in The Story of a Mother are quintessential Andersen. Within the first few paragraphs, the theme is clear and features his imagery-rich language: „Stary zegar wył i wył, ogromny ciężar zegara ołowiany zsunął się prosto na podłogę, bum! i zegar także stał w milczeniu.” Although Andersen had written about dying children before, he struggled with the ending of this story, even in the handwritten copy he delivered to the printer. His first version was what you might call a happy ending: the mother wakes to find it was all a dream. He immediately crossed this out and replaced it with: „And Death went with her child into the ever-flowering garden”. Still unsatisfied, he changed „ever-flowering garden”, a synonym for paradise, to „the unknown land”. A Danish critic recently described this creative shift as „how to punk your sugar-coated sentiment into salty liquorice” – a fitting metaphor for Andersen’s refusal to settle for sentimentality. Today, the story is not as well known as some of his other tales, yet its influence in its own time was undeniable. It was translated into Bengali as early as 1858 and became popular in India. When Andersen turned 70 in 1875, one of his gifts was a polyglot edition of the story translated into no less than 15 languages – a testament to its global reach. Możesz przeczytać pełną wersję Opowieści matki, tutaj.

Kometa — od ciszy do poetyckiej prozy i pytanie o duszę

Holger Berg, special consultant at The Hans Christian Andersen Centre, University of Southern Denmark No spectacular comets appeared in 1869, but the year nevertheless stands out in literature thanks to The Comet. Andersen’s reflective tale of the cosmos and the soul begins simply. A boy blows bubbles while, by the light of a candle, his mother seeks signs about the child’s life expectancy. Childlike delight and superstition live side by side in their home. More than 60 years pass. The boy has become an elderly village schoolmaster. He teaches history, geography and astronomy to a new generation, bringing each subject vividly to life. Science has not destroyed his wonder – it has deepened it. Then the very same periodic comet returns. What allows The Comet to echo across the ages is, paradoxically, its quiet, unassuming form. In earlier works, Andersen confronted one of the great fears of his age: that a comet might strike the Earth and end human civilisation. He responded either with comedy or with factual precision, but neither approach proved moving. In 1869, he shifted away from satire and intellectual argument and towards poetic prose. Meaning now emerged through suggestion rather than debate. He also abandoned the romantic mode of his youth, in which the moon, the morning star and other celestial bodies directly commented on earthly affairs. Part of my fascination with this tale lies in the four surviving manuscripts. Andersen gradually developed his narrative from a quaint scene in a village classroom into a life story with genuine cosmological reach and this can be seen in each version of the story. It’s often said that a human life is merely a glimpse when measured against astronomical time. In Andersen’s time, people quoted the Latin expression homo bulla: the human being is but a soap bubble. To this familiar poetic image, Andersen in his second manuscript added the comet. Against the brevity of the bubble, he set the vastness of the comet’s arc – and with it, the question of where the human soul travels once it leaves the body. Andersen achieved his narrative breakthrough in late January of 1869 through a shift in both theme and structure. In the third manuscript, he added a final paragraph nearly identical to the opening. This narrative circle matches the subject at hand: „Everything returns!” the schoolmaster teaches us, be it periodic comets or historical events. And yet the tale ends by imagining what does not return: the „soul was off on a far larger course, in a far vaster space than that through which the comet flies”. Andersen invites us to gaze upward with the openness of a child. And raises profound questions about what it means to be human, both in this world and, for spiritually inclined readers, in whatever may lie beyond it. Tutaj możesz przeczytać pełną wersję Komety, tutaj oraz posłuchać podcastu o tej historii.

Cień — odwrócona baśń o pragnieniu i władzy

Jacob Bøggild, associate professor at The Hans Christian Andersen Centre, University of Southern Denmark The Shadow by Hans Christian Andersen was first published in 1847. In some ways, it is Andersen’s darkest tale. The character the reader is led to believe is the protagonist is known only as “the learned man,” a figure never given a name, whereas his shadow – which breaks away from him – gives the tale its very title. At the end of the story, the shadow has the learned man executed and marries the daughter of a king, implying that they will rule her country together. Thus, the shadow triumphs in the manner of a genuine fairy-tale protagonist, while his former master dies miserably. But the tale is not solely dark and tragic. The scene in which the shadow separates from the learned man is perfectly choreographed in accordance with the way a shadow follows every movement of the body that casts it. Afterwards, it irks the learned man that he has lost his shadow, but since he is visiting a country with a warm climate he soon grows a new one. And one reason the shadow can seduce the princess is that he is a wonderful dancer – he is, of course, ever so light on his feet. Throughout the tale, Andersen treats each impossible occurrence as though it were entirely natural, and the effect is extremely funny (as well as uncanny). In traditional fairy tales, the protagonist often leaves home because some imbalance has occurred. Away from home, out in the wide world, the protagonist must accomplish a number of tasks. The happy ending usually means that the character finds a new home, often by marrying a princess and becoming ruler of half a kingdom. In The Shadow, the learned man is already away from home at the beginning, visiting a country with a hot climate before returning to his own homeland with a cold one. It is here that his former shadow appears and manipulates him into exchanging roles, making the learned man literally the shadow of a shadow. The two then travel to a spa. The learned man is once again far from home, and it is there that he dies. The shadow, on the other hand, begins its story “at home”, since its home is wherever the learned man is. It then separates itself, goes out into the world and becomes highly successful – albeit through mischief. Its ultimate triumph comes when it establishes a new home for itself by marrying the princess. The Shadow is a reversed fairy tale in every possible sense. The way Andersen executes this reversal is a masterpiece and bears witness to his acute awareness of genre conventions and narrative structures – something that has, unfortunately, rarely been recognised as fully as it deserves. You can read the full version of The Shadow, here.

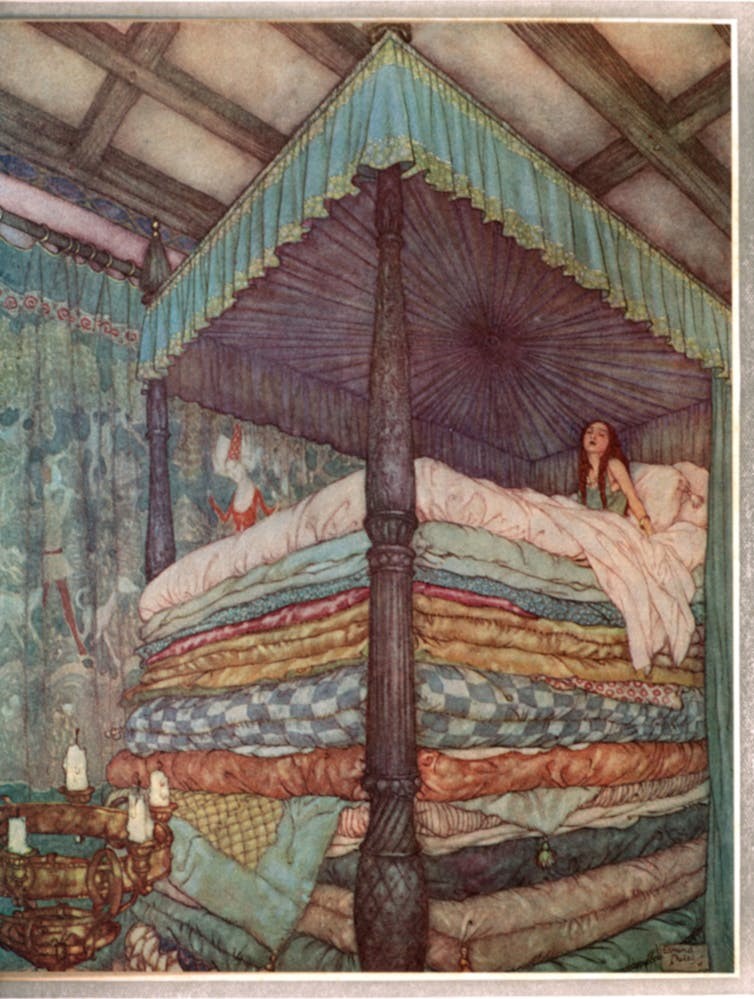

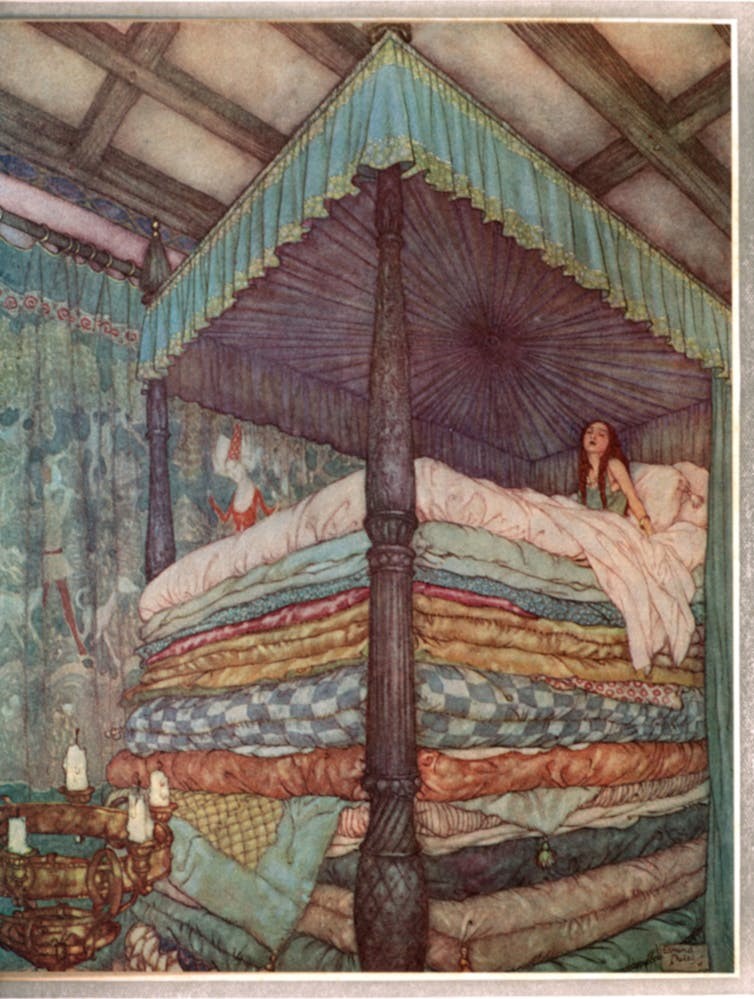

Księżniczka na grochu — prawdziwość i fikcja w krótkiej baśni

Sarah Bienko Eriksen, postdoctoral researcher at The Hans Christian Andersen Centre, University of Southern Denmark Księżniczka na grochu miała pecha, że stała się tak popularna, że wielu ludzi nie zagląda do niej. To niedopatrzenie. A zważywszy, że opowieść liczy mniej niż 350 słów — krótsza niż artykuł, który czytasz — to problem łatwy do naprawienia. Baśń zaczyna się od światowego poszukiwania prawdziwej księżniczki przez księcia. Spotkał wielu nadziei na drodze, lecz nie były one „prawdziwe”, a dla niego jedynie „prawdziwa” wystarczy. Słowa „realne” i „prawdziwe” (po duńsku riktig/virkelig) pojawiają się w tej miniaturze łącznie dziewięć razy — co zaprzecza pewnym truizmom o dobrym pisaniu i temperamencie życia. Gdy na zamek przybywa kandydująca księżniczka pewnego burzliwego wieczoru, krople deszczu spływają z jej włosów i z jej pięt, dosłownie uosabia problem, jak stwierdzić, czy coś jest realne. Czy widzimy to na pierwszy rzut oka? Czy można to zaobserwować poprzez zachowanie? Czy trzeba to po prostu poczuć? Aby sprawdzić, czy gość jest prawdziwym artefaktem, królowa testuje ją łóżkiem dla księżniczki: 20 kołder na 20 materacach i na samym dole pojedynczy groch. Nie perła ani diament, ale najniższy z domowych przedmiotów. Gość nie przegapia jednak niczego, budzi się siną i obolałą i gorszą od przybycia. Dwór od razu zadowolony — tylko prawdziwa księżniczka mogła być tak wrażliwa! — a mimo to cała ta próba nie zbliża ich do faktycznego wykrycia jednej: to jej zdolności obserwacyjne, które przechodzą test, nie ich. Wygląda na to, że prawda wie sama, kim jest. Nie musimy zgadywać, co się stanie dalej, ale co nastąpi po ślubie? Tutaj znajdujemy najbardziej innowacyjny wkład Hansa Christiana Andersena w tę tradycyjną baśń: mianowicie groch dostaje własne zakończenie, zyskując miejsce w Królewskim Muzeum „gdzie go wciąż można zobaczyć, pod warunkiem że nikt go nie zabrał”. Duńczyk czytający tę historię w 1835 roku nie mógł nie zauważyć tego odniesienia do kradzieży w 1802 roku duńskiego skarbu narodowego — Złotych Rogów Gallaha — z tego samego miejsca. Mniej oczywiste jest to, że dzięki temu odniesieniu Andersen „wyjmuje bańkę” z baśni i wrzuca groch do realnego świata. Czy to czuliśmy? Być może nie. A może to groch został skradziony. „Teraz to była prawdziwa historia!” — kończy się opowieść, z pełną świadomością. Nie była to prawdziwa historia, uwaga, ale stan „prawdziwej fikcji”. (A jeśli chcemy to przetestować samodzielnie, to nie wina Andersena, że rzeczywisty artefakt zginął z Królewskiego Muzeum.) W przeciwieństwie do naszej księżniczki, ta baśń nie oferuje czystego zakończenia, co jest właśnie bogactwem wielkiej sztuki: skłania do refleksji, ukrywa cud w skromnym szczególe i nigdy nie jest naprawdę skończona, zachęcając nas do wspólnej zabawy w szczęśliwe zakończenie. Tutaj możesz przeczytać pełną wersję Księżniczki na grochu.