Left for dead on Everest: the 1996 blizzard that killed 12 and the doctor who clawed his way back

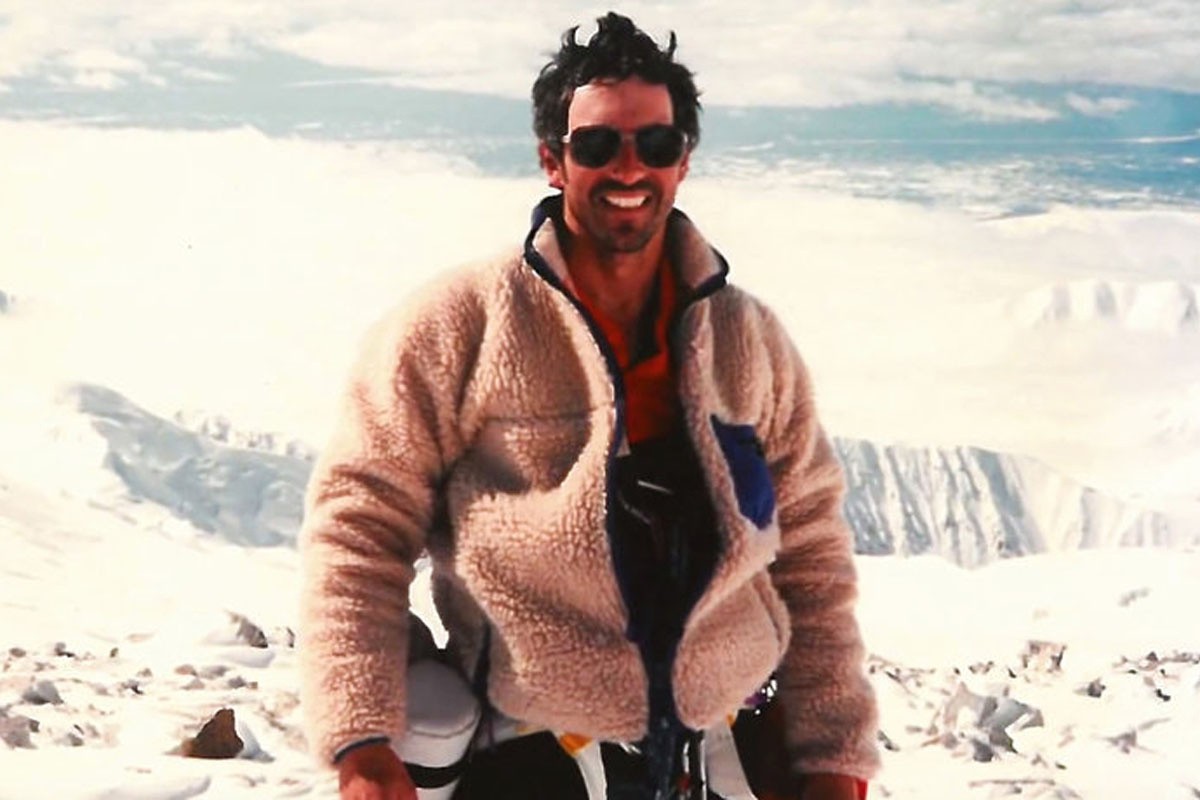

In May 1996, Everest turned deadly for climbers when a ferocious blizzard swept the summit area and claimed 12 lives. Among the victims was Beck Weathers, a 49-year-old pathologist who had spent years chasing the Seven Summits dream. He was left on the South Col to wait while the others pressed toward the summit, with a promise that he would be retrieved on the way back. He reluctantly agreed, lying in the snow as the storm closed in. The rescue plan failed as conditions worsened, and the story of those hours—and his improbable survival—would become legend, later inspiring the 2015 film Everest.

In This Article:

A vow to stay put and a brutal test of survival

Beck Weathers joined Rob Hall’s eight‑person team from Adventure Consultants. The morning ascent felt doable, but Beck’s eye problem would complicate everything: laser surgery had left his cornea deformed at altitude, and by night he could barely see. Hall ordered him to stay on the trail while the others continued toward the summit, promising to fetch him on the way back. Beck agreed, lying in the snow on the South Col and turning down offers of help, determined to keep his word. Yet a sudden storm would erase any chance of a simple rescue.

The night of whiteout: a rescue that nearly failed

As darkness fell, winds roared past 150 km/h and temperatures plunged below -40°C. Climbers became disoriented, lost consciousness, and froze where they stood. Mike Grum reached Beck first, lifting him toward the camp, but Beck’s right hand began to freeze after a glove came off, and a gust knocked him back into the snow. A Russian guide spotted the silhouette and assumed Beck was dead, a judgment that another guide would echo the next morning when he found him again, unconscious and encased in ice.

Hypothermia, a phone call, and a second life

Just before dawn, Beck’s wife had begun realizing that his absence could end their marriage; at about 6 a.m., Adventure Consultants notified her of his death. But Beck was not dead. He slipped into a hypothermic coma and, after more than 20 hours in the snow, woke as his body warmed enough to revive him. He dragged himself back to the base camp, his face black with frost and his body numb from cold. He was flown to Kathmandu for life‑saving surgery: the right arm, several fingers on the left hand, parts of his toes, and part of his nose were removed, and surgeons rebuilt his nose using skin from his neck and ear.

A new life after Everest: healing, family, and flight

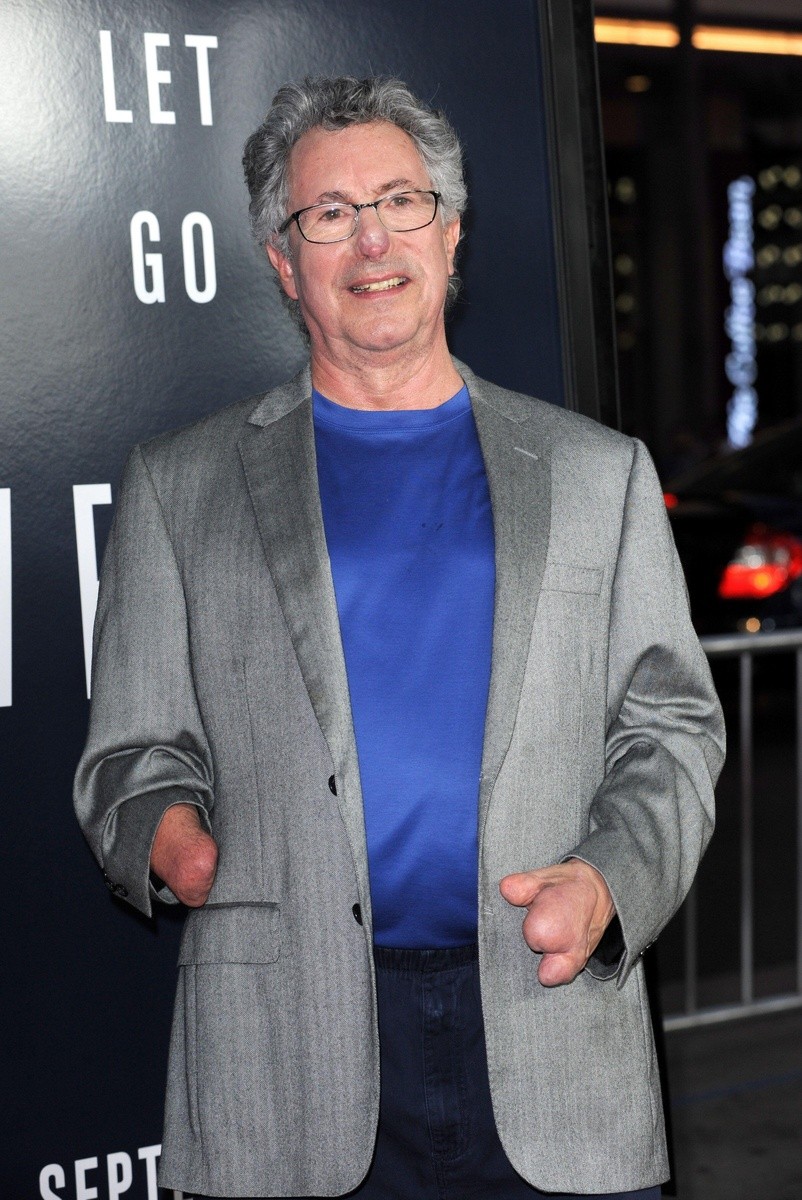

Back home in Dallas, Beck rebuilt his life around family and a quieter future. He reconciled with his wife, promised to change his lifestyle, and stepped away from climbing. He discovered a new passion: flying, enjoying the freedom of piloting a Cessna 182‑Turbo and looking down on the world from above. He reached his 70s, then 78, still in good health, but he never returned to extreme sports. His home holds no climbing gear—except for a photograph from May 1996 showing him reuniting with his wife, his face marked by frostbite as a reminder of what happened. The Everest disaster remains a cultural touchstone, and Beck Weathers’ survival helped shape the 2015 film Everest, a testament to human resilience in the face of nature’s fury.