In Alaska, You Can Earn About $6,000 a Month Before Taxes—Yet Groceries Could Eat It Away

In Alaska, you can earn about $6,000 a month before taxes, and July data put the average hourly wage at $31.34. On paper, those numbers look strong. But Alaska is a land of contrasts: prices for food, heating, and shipping run high, and overtime can push take‑home pay up—yet it often doesn’t fully close the gap with the cost of living. This story isn’t just about numbers. It’s about real people balancing budgets, flights, and futures in a place where every penny travels a long way.

In This Article:

Prices Rise in Alaska Because Goods Must Travel From the Mainland

Prices rise in Alaska because goods must travel from the mainland. In a typical Anchorage hypermarket, organic peppers are around $3, 900 grams of lemons are about $5–6, and a bunch of parsley runs around $1.50. Local pork is often about $5.50 per kilogram on sale, and milk can be around $1. Transport costs mean fresh produce and perishable foods stay expensive. With costs like these, even people earning more can feel stretched. The distance between paycheck and daily needs is real.

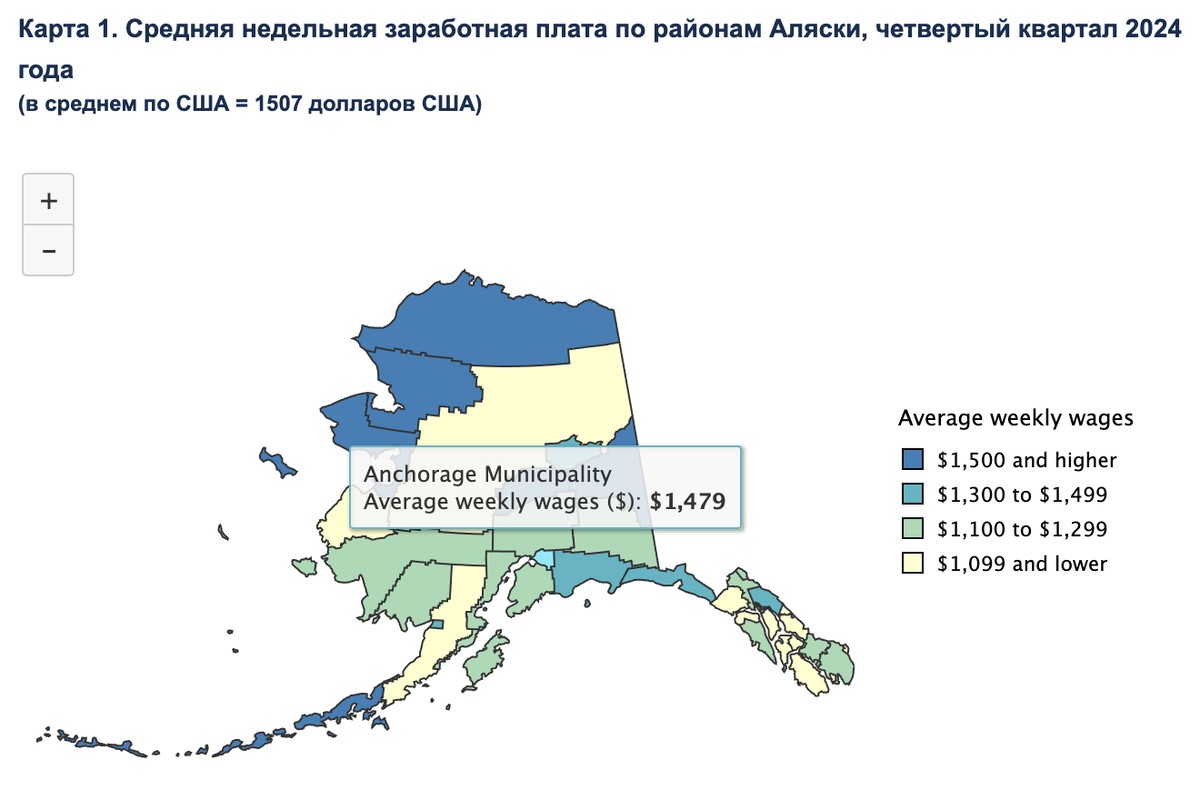

Wages in Alaska Are Not Uniform: The Numbers Tell a Complex Story

The wage picture is not uniform. The headline figures show monthly earnings exceeding $5,000, with July hourly wages around $31.34. However, the reality depends on the job and location. When overtime is common, monthly pre‑tax income can reach about $6,530. Alaska law caps the workweek at 40 hours and 8 hours per day; overtime is voluntary and paid at 1.5x. Government workers also receive a northern allowance of about 25%. Anchorage alone accounts for roughly 46% of all jobs, with average weekly pre‑tax earnings around $1,479, just under the national average. Statewide weekly earnings are about $1,430, translating to roughly $6,000 per month.

A Human Thread Behind the Numbers

A personal thread runs through the numbers. A classmate in New York says, “You won’t believe it—I haven’t eaten out in three weeks. It’s all pizza, and I’m saving.” In the United States, middle‑income families spend about 13.5% of their budget on food, including home cooking and meals out; low‑income families spend about 32.6%. People hope for vacations and comfortable homes, but rising costs push families to choose carefully. The idea that American youth must leave the family home at 18 to be independent is, at times, a myth. Overall, Alaska wages show a paradox: high nominal pay, yet a cost of living that erodes earnings, and a patchwork of benefits and obligations that shape what people finally take home.