Forgotten by All: The Last Nicoleno Woman Survived 18 Years Alone on a Harsh California Island—Only to Face a Grim Fate Upon Rescue

In 1835, as Nicoleno families were hurried onto a whaling schooner named Peor es Nada—'Better than nothing'—the ship vanished over the horizon, and one woman was left behind on San Nicolas Island. She would live there alone for eighteen years, the last of her people. When rescuers finally arrived and carried some Nicoleno to the mainland, it carried a cruel irony: the world they reached would not save them. Those brought to the mainland died quickly from unfamiliar diseases, and the Nicoleno culture, and the language, vanished.

In This Article:

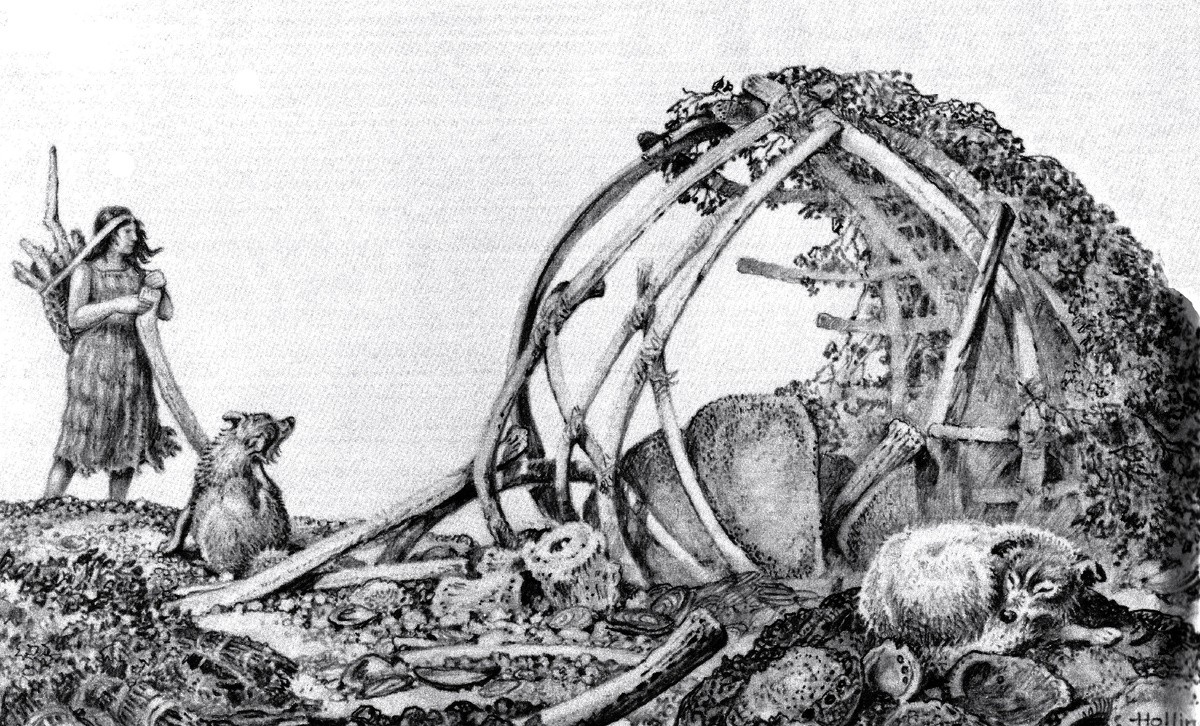

An Evacuation That Forgot One Woman

San Nicolas is not a tropical paradise. It is the most remote of California’s islands, a windswept strip of land often wrapped in fog, with cliffs, dunes, and a hard grassland that bears witness to the sea’s bite. Juana Maria built two shelters: a natural cave for storms and a sturdy house fashioned from whale bones—ribs as the support beams, sealskin as the roofing. In 1939 archaeologists uncovered this whale-bone house, a home that could withstand the fiercest ocean winds. Her diet leaned on the sea: seal meat and fat provided essential protein and warmth. She hunted seabirds, used their feathers for clothing, and bones for tools. The coastline yielded fishing and shellfish, and she knew edible roots and plants. She dried meat and fish in the sun and stored seal fat in dried bladders. She made baskets and containers from grasses, waterproofing them with natural bitumen she found on the shore.

Island Ingenuity: Juana Maria’s Self-Made Life

Juana Maria kept dogs—raised from pups she found on the island—who accompanied her in the hunt and offered companionship in the long years alone. She fashioned tools from stone and bone, stitching clothing from hides and feathers with bone needles. Her signature garment was a cape woven from greenish-blue seabird feathers, a feat of craft that even her rescuers admired. Her daily life was a practical, self-reliant civilization, built from the resources the island offered.

Rescue and Ruin: The Mainland Welcome That Killed

By the mid-1800s, sailors were telling tales of a ‘wild woman’ on San Nicolas. George Nidever, a hunter, chased the legend and finally found her at her hut while she was preparing a seal. Rather than flee, she welcomed the strangers with a smile and offered roasted roots, greeting them as guests. They transported her to Santa Barbara and lodged her in the home of Nidever. The Nicoleno language had died with the island; she could not communicate with the people around her. On October 19, 1853—seven weeks after arriving on the mainland—she died of dysentery. A sudden shift to a Western diet—beef, corn, apples, grapes—overwhelmed a gut that had adapted to seals and island plants.

The Cost of Survival: The Last Nicoleno Voice Fades

With her death, the Nicoleno language disappeared; only four Nicoleno words and two songs are known today. She was baptized on the mainland and given the Spanish name Juana Maria, but her true name remains unknown. She was buried in an unnamed grave on the Nidevers’ family plot near the Santa Barbara Mission. Her story is a stark reminder of the cultural cost of rescue—how good intentions can erase a people when contact with new diseases and diets overrides centuries of adaptation.