Computers Made from Human Brain Tissue Are Coming — Are We Prepared?

Three forces are converging to push biology toward the computing frontier. Venture capital is flowing into anything adjacent to AI, making speculative ideas suddenly fundable. Techniques for growing brain tissue outside the body have matured, with the pharmaceutical industry jumping on board. And rapid advances in brain–computer interfaces are blurring the line between biology and machines. The result is a new kind of hardware built from living tissue—often described as "biocomputers"—that can perform tasks from simple games to basic speech recognition. Yet questions linger: Are we witnessing genuine breakthroughs, or another round of tech-driven hype? And what ethical challenges arise when living brain tissue becomes a computational component?

In This Article:

From Neurons to Organoids: The Long Road to Biohybrid Computing

For almost 50 years, neuroscientists have grown neurons on arrays of tiny electrodes to study how they fire under controlled conditions. Researchers began experimenting with two-way communication between neurons and electrodes in the early 2000s, sowing the seeds of a bio-hybrid computer. Progress stalled until a new strand of research took off: brain organoids. In 2013, scientists demonstrated that stem cells could self-organize into three-dimensional brain-like structures. These organoids spread rapidly through biomedical research, increasingly aided by "organ-on-a-chip" devices designed to mimic aspects of human physiology outside the body. Today, using stem-cell-derived neural tissue is commonplace—for drug testing and developmental research. Yet the neural activity in these models remains primitive, far from the organized firing patterns that underpin cognition or consciousness in a real brain. While complex network behavior is beginning to emerge even without much external stimulation, experts generally agree that current organoids are not conscious, nor close to it. The field entered a new phase in 2022, when Melbourne-based Cortical Labs published a high-profile study showing cultured neurons learning to play Pong in a closed-loop system. The paper drew intense media attention — less for the experiment itself than for its use of the phrase "embodied sentience". Many neuroscientists said the language overstated the system's capabilities, arguing it was misleading or ethically careless. A year later, a consortium of researchers introduced the broader term "organoid intelligence". This is catchy and media-friendly, but it risks implying parity with artificial intelligence systems, despite the vast gap between them. Ethical debates have also lagged behind the technology. Most bioethics frameworks focus on brain organoids as biomedical tools—not as components of biohybrid computing systems. Leading organoid researchers have called for urgent updates to ethics guidelines, noting that rapid research development, and even commercialisation, is outpacing governance. Meanwhile, despite front-page news in Nature, many people remain unclear about what a "living computer" actually is. Companies and academic groups in the United States, Switzerland, China and Australia are racing to build biohybrid computing platforms. Swiss company FinalSpark already offers remote access to its neural organoids. Cortical Labs is preparing to ship a desktop biocomputer called CL1. Both expect customers well beyond the pharmaceutical industry—including AI researchers looking for new kinds of computing systems. Academic aspirations are rising, too. A team at UC San Diego has ambitiously proposed using organoid-based systems to predict oil spill trajectories in the Amazon by 2028. The coming years will determine whether organoid intelligence transforms computing or becomes a short-lived curiosity. At present, claims of intelligence or consciousness are unsupported. Today's systems display only a simple capacity to respond and adapt, not anything resembling higher cognition. More immediate work focuses on consistently reproducing prototype systems, scaling them up, and finding practical uses for the technology. Several teams are exploring organoids as an alternative to animal models in neuroscience and toxicology. One group has proposed a framework for testing how chemicals affect early brain development. Other studies show improved prediction of epilepsy-related brain activity using neurons and electronic systems. These applications are incremental, but plausible.

Organoid Intelligence: The Risk of Parity with AI

A year after Cortical Labs’ Pong demonstration, researchers broadened the conversation with a new label that captures the field’s ambition and its limits: "organoid intelligence". This term is catchy and media-friendly, but it risks implying parity with artificial intelligence systems, despite the vast gap between them. Ethical debates have also lagged behind the technology. Most bioethics frameworks focus on brain organoids as biomedical tools—not as components of biohybrid computing systems. Leading organoid researchers have called for urgent updates to ethics guidelines, noting that rapid research development, and even commercialisation, is outpacing governance. Meanwhile, despite front-page news in Nature, many people remain unclear about what a "living computer" actually is. What counts as intelligence? When, if ever, might a network of human cells deserve moral consideration? And how should society regulate biological systems that behave, in limited ways, like tiny computers? The technology is still in its infancy. But its trajectory suggests that conversations about consciousness, personhood and the ethics of mixing living tissue with machines may become pressing far sooner than expected. Bram Servais, PhD Candidate Biomedical Engineering, The University of Melbourne

A Global Race to Build Biohybrid Computers

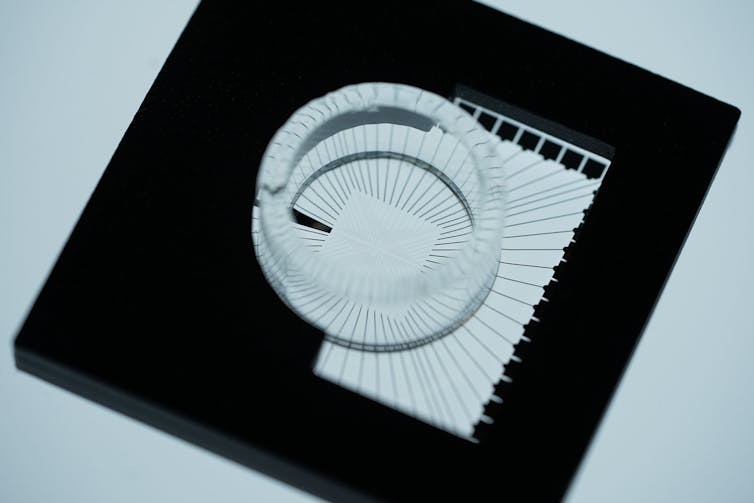

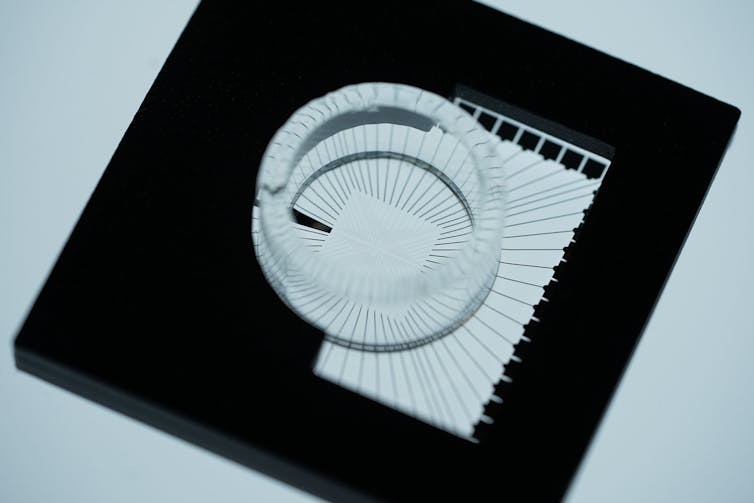

Companies and academic groups in the United States, Switzerland, China and Australia are racing to build biohybrid computing platforms. Swiss company FinalSpark already offers remote access to its neural organoids. Cortical Labs is preparing to ship a desktop biocomputer called CL1. Both expect customers well beyond the pharmaceutical industry—including AI researchers looking for new kinds of computing systems. Academic aspirations are rising, too. A team at UC San Diego has ambitiously proposed using organoid-based systems to predict oil spill trajectories in the Amazon by 2028. The coming years will determine whether organoid intelligence transforms computing or becomes a short-lived curiosity. At present, claims of intelligence or consciousness are unsupported. Today's systems display only a simple capacity to respond and adapt, not anything resembling higher cognition. More immediate work focuses on consistently reproducing prototype systems, scaling them up, and finding practical uses for the technology.

Ethics, Intelligence, and Governance in a Living Computer Era

Much of what makes the field compelling—and unsettling—is the broader context. As billionaires such as Elon Musk pursue neural implants and transhumanist visions, organoid intelligence prompts deep questions. What counts as intelligence? When, if ever, might a network of human cells deserve moral consideration? And how should society regulate biological systems that behave, in limited ways, like tiny computers? The technology is still in its infancy. But its trajectory suggests that conversations about consciousness, personhood and the ethics of mixing living tissue with machines may become pressing far sooner than expected. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Credits and Republication Note

Bram Servais, PhD Candidate, Biomedical Engineering, The University of Melbourne. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.