Cephalopods Pass a Test Designed for Human Children

An experiment from Cambridge researchers reframes what counts as smart in the sea. In a version of the Stanford marshmallow test, common cuttlefish learned to delay gratification to secure a better meal later. Their capacity to wait—often 50 to 130 seconds—rivals the self-control shown by chimpanzees, crows, and parrots in similar tests.

In This Article:

A New Marshmallow Test for Cuttlefish: The Experimental Setup

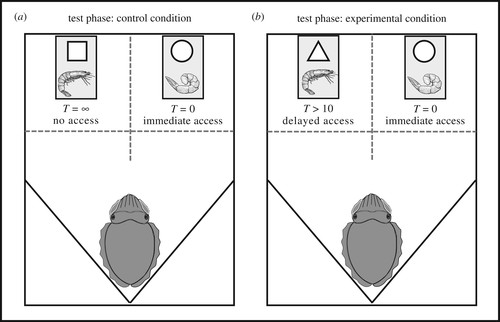

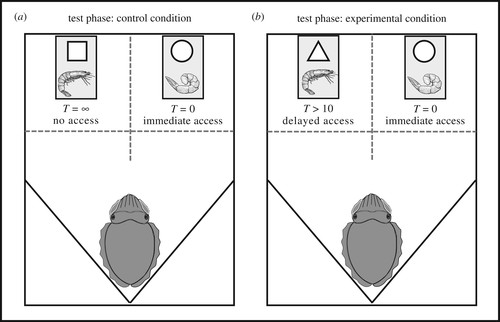

Six common cuttlefish were placed in a tank with two enclosed chambers behind transparent doors, each marked with a symbol: a circle means the door opens immediately, a triangle opens after a delay (10–130 seconds), and a square keeps the door closed forever (the control). Behind one door was a less-preferred snack (raw king prawn); behind the other was a more enticing reward (live grass shrimp). In the test condition, the prawn was behind the door that opened immediately, while the grass shrimp could be accessed only after the delay. If a cuttlefish went for the prawn, the shrimp was removed. In the control, the shrimp remained inaccessible behind the square door.

Waiting for the Better Reward: What the Results Show

All six cuttlefish in the test condition waited for the preferred food, tolerating delays, while none did so in the control. Delays reached 50–130 seconds, which Schnell notes are comparable to those seen in large-brained vertebrates such as chimpanzees, crows, and parrots. "Cuttlefish in the present study were all able to wait for the better reward and tolerated delays for up to 50–130 seconds, which is comparable to what we see in large-brained vertebrates such as chimpanzees, crows, and parrots," Schnell explained.

Why Do Cuttlefish Delay Gratification?

In other species, delayed gratification has been linked to tool use, food caching, and social competence. Cuttlefish do not rely on tools or caching, nor are they especially social. Researchers speculate that this ability may be a byproduct of foraging: they spend most of their time camouflaged, waiting, and only briefly foraging, which exposes them to predators. They break camouflage when they forage, so they are exposed to every predator in the ocean that wants to eat them. Delaying gratification may help optimize foraging by waiting for higher-quality prey.

Memory, Planning, and the Path Forward

Evidence of episodic-like memory has been found in cuttlefish, and in 2024 scientists reported the first observation of false memories. The team published their findings in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The researchers say further work is needed to determine whether cuttlefish can plan for the future. A version of this article first appeared in March 2021.