Captured as Prize: The brutal history of women in war and the harem

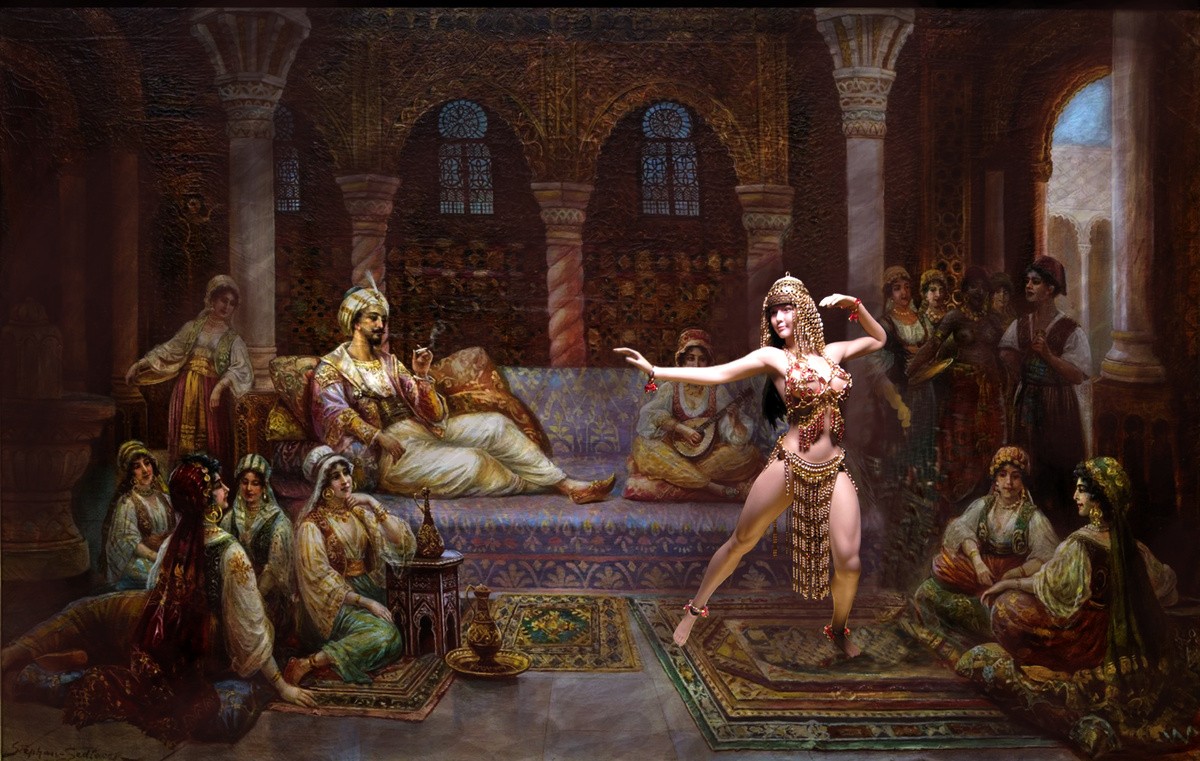

Behind the romance of grand harems and velvet courts lies a harsher truth: in many ancient Eastern worlds, a woman's life was valued not for her humanity but for her utility as property. Conquerors often claimed wives and daughters as spoils of victory. A saying attributed to Genghis Khan—“the greatest joy for a man is to defeat his enemies and take their daughters and wives”—offers a stark window into a worldview that shaped centuries of warfare and marriage. This look across empires shows a spectrum: some women were kept as living ornaments, some were exchanged in diplomacy, and some wielded political leverage. Yet the fate of captives tended to hinge on power, diplomacy, and the shifting tides of conquest.

In This Article:

Most rulers kept harems behind the walls of their capitals

Not every eastern ruler chose to bring the entire court on campaign. Marching with courtiers would slow the army and complicate logistics. Along the march, there were chances to meet peasant girls or women along the way, offering a grim variety of life rather than a formal policy of conquest. Because of these realities, harems often stayed home; even when cities were looted, the capture and redistribution of a harem was not the standard reward of victory. Yet in nomadic, horse‑based cultures, war could resemble a grand migration, with the harem traveling alongside the army when the times demanded.

Kesedag, 1243: Baiju and the Mongol loom over a defeated harem

In the 1243 clash between Seljuks and Mongols at Kesedag, the Mongol temnik Baiju routed the army of the sultan of Konya and took his massive harem as captives. Among them was Gurju-khatun, the chief wife, who was treated with respect and returned to her husband after the peace treaty. The defeated sultan Kay-Khosrow II even ceded half his realm and paid tribute. But Mongol practice often distributed wives and daughters to brothers and sons of the victors. Another example: Batu Khan demanded the living husband of Evpraksia, the wife of a Russian prince, during his campaign in the Ryazan principality. In this world, the fate of captured women could be molded by power and circumstance—and sometimes diplomacy and mercy mattered more than mere plunder.

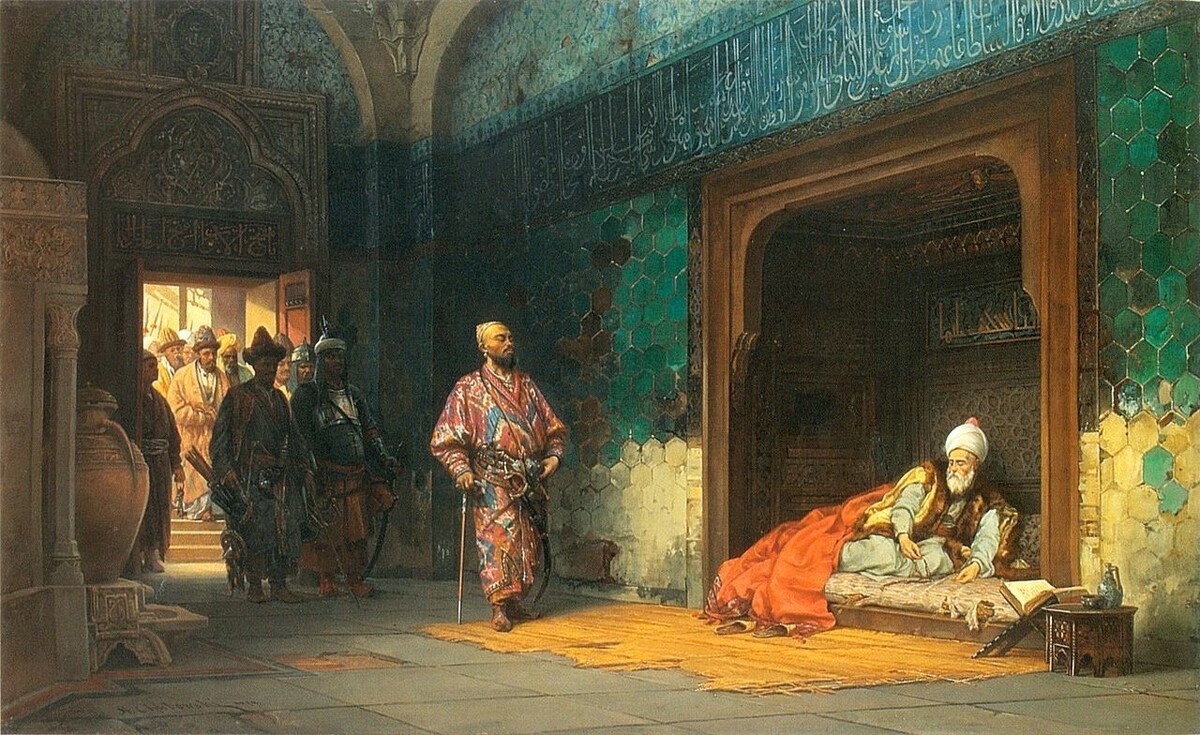

Chaldiran 1514: contested fates of sultan’s wives

After the Battle of Chaldiran, Timur captured the sultan Bayezid along with his harem. Opinions on what happened next diverge across cultures. European writers claim the sultan’s Serb wife, Olivera, was forced to serve naked at a banquet. Ottoman chroniclers insist the sultan shattered himself on the iron bars of a cage in humiliation. Ibn Arabshah, captured by Timur in Damascus, claims the sultan’s treatment was honorable. Samarqand chronicles say Olivera was treated with dignity and eventually released by ambassadors from her brother, the Serbian prince. Regardless, Selim I’s aftermath of Chaldiran was harsher toward Tadzhli-khatun and Behruze-khanum, elder wives of the Iranian shah Isma’il. The sultan reportedly used them on his bed and, when they tired of him, arranged marriages for them to Istanbul aristocrats.

A survivor’s story and a strange anthropology

Even in these brutal histories, there were exceptions that reveal human complexity. Tamerlane took Saray-mulk Khanum, the wife of the murdered emir Husayn, as his own. They lived together for nearly forty years, and she never spoke of her first husband with pain. Anthropologist Drobyshevsky relates a curious tale about tribes that attacked a village to seize men for wives; in a strange twist, the captured women aided the attackers by helping to defeat their own husbands. These fragments remind us that history’s most intimate moments can reveal surprising agency, resilience, and humanity amid violence.