Burning Walls into Glass: The Great European Fort Vitrification Mystery

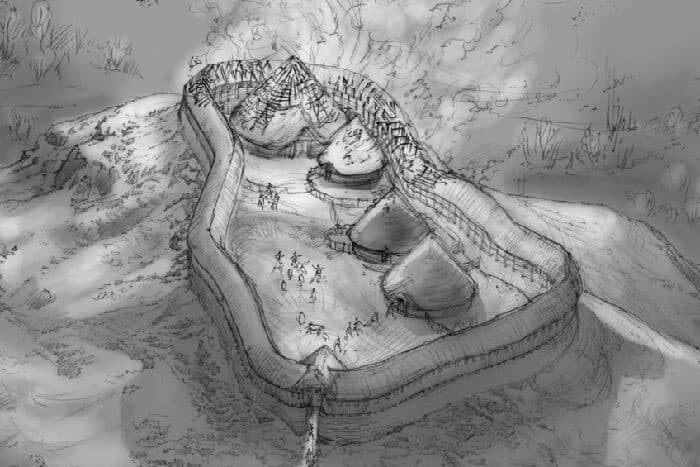

Across Bronze and Iron Age Europe, hundreds of stone forts stood watch on hilltops. Today, roughly 200 of these ruins carry a haunting signature: the walls were heated so intensely that the stones fused into a single glassy, monolithic block. For about 250 years, vitrified forts have been one of archaeology’s most enduring mysteries. Temperature estimates place the heat near 1200°C, and the glass-like bond continues to baffle researchers as they search for a purpose behind the flames.

In This Article:

What is a vitrified fort? The glassy bond that holds the stones

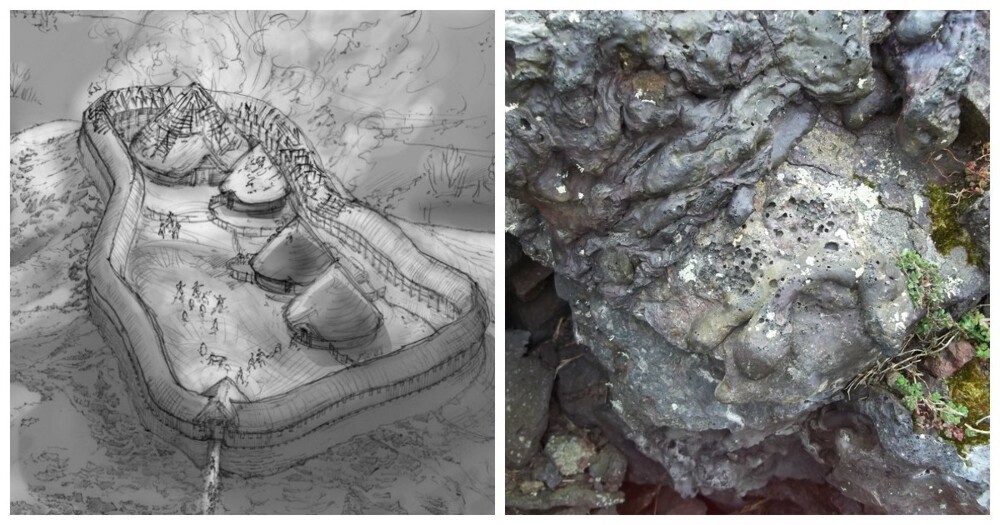

Vitrified forts are the remnants of dry-stone construction, built without cement or mortar. The heat scorched the stones so intensely that they fused into a glassy, seamless mass, binding the walls into a single block. Initially, many assumed the damage came from enemy fire, but the resulting glassy bond is what actually holds the structure together. Today, more than 200 examples are known across Western and Northern Europe, revealing a wider phenomenon beyond Scotland.

The mystery deepens: accidental fire or deliberate design?

Scholars are divided. Some argue vitrification happened as a side effect of other activities—metalworking smelts or large signal fires. Others see it as a purposeful construction technique, designed to harden the walls. What is clear is that there is no cement binding the joints; the bond appears to come from heat acting on the stones themselves.

The 1930s experiments that sparked the debate

In one of the first controlled tests, Wallace Thornicroft and V. Gordon Childe built a wall of stone slabs with wooden cores and set it aflame. The fire burned for three hours, the wall collapsed, and charred timber fragments were found among the debris. Researchers estimated temperatures around 1200°C. Subsequent studies showed that simple burning of a wooden frame isn’t enough to explain the vitrification; the heat must be sustained for days in a closed space, with earth, clay, and peat filling the gaps. This makes deliberate heating plausible, not a random fire or an enemy attack.

A new theory: vitrification as engineered strength and a wider European phenomenon

Today, some researchers suggest that heating sandstone can cause its particles to fuse into a dense glassy mass, increasing durability. If correct, vitrified forts were an ingenious engineering solution, not vandalism or accident. The phenomenon is broader than Scotland: more than 200 known examples stretch across Western and Northern Europe, underscoring a forgotten high-tech approach to fortification.