Ball's Pyramid: The Sea's Tallest Rock That Kept a Living Secret Alive

Imagine sailing the Tasman Sea in the 18th century when a dark giant rises from the water—a basalt pillar that points toward the sky. This is Ball's Pyramid, the tallest rocky island in the world that remains completely surrounded by water, rising 562 meters above the waves. Its true surprise lies not in height but in life: on this remote outcrop, a creature once thought extinct for nearly a century clings to life here, the tree lobster Dryocochelus australis.

In This Article:

A basalt spear above the Tasman Sea

Ball's Pyramid stretches about 1,100 meters long and 300 meters wide, curving like a slender crescent and rising in the Tasman Sea roughly 600 kilometers east of Australia. Its surface is basalt—the cooled lava of an ancient eruption that built a volcanic island long ago. The rock stands as a solitary monument, a remnant of a volcano that rose, then quieted, leaving behind a towering pillar in the sea.

From eruption to enduring monolith

Six to seven million years ago, a submarine volcano rose and spilled lava into a vent beneath the sea. As the magma cooled, it formed a basalt plug—the seed that would become Ball's Pyramid. Over time, wind and waves wore away the surrounding softer rock and sharpened the hard core into a tall, durable monolith. Today Ball's Pyramid stands as a vivid example of the penultimate stage of volcanic island leveling—a high, solitary remnant of a vanished land.

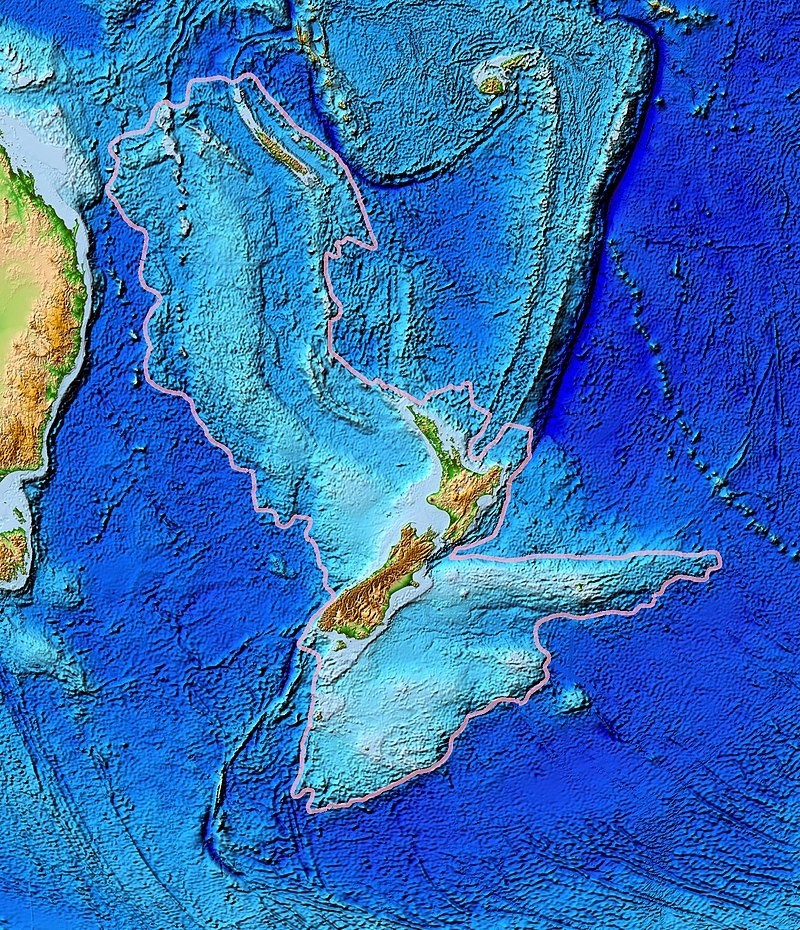

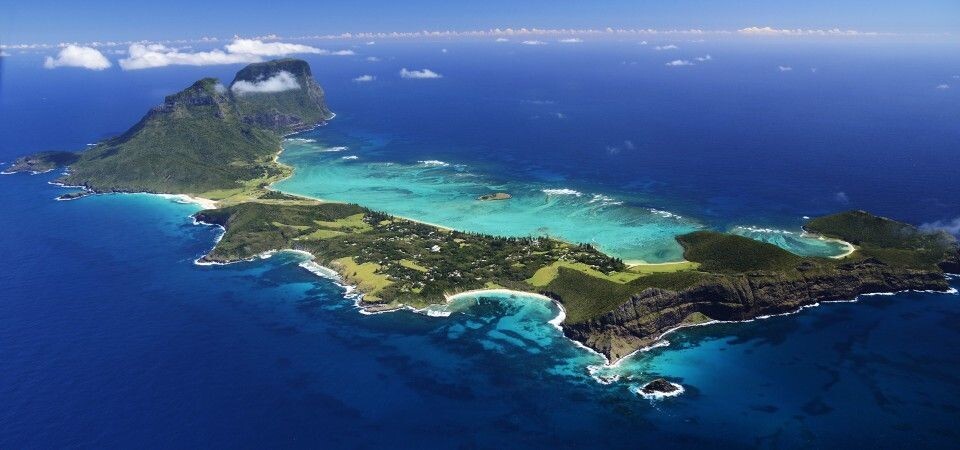

Zealandia, Lord Howe, and the last surface of a sunken continent

Two tens of kilometers away sits Lord Howe Island, a larger neighbor that often sits on the horizon when you look toward Ball's Pyramid. A growing hypothesis suggests Ball's Pyramid and the surrounding islets are among the last exposed pieces of Zealandia, a submerged microcontinent. Zealandia was a microcontinent with thin crust that was crumpled and submerged as the Indo-Australian and Pacific plates moved apart. Today, about 94% of Zealandia lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. Ball's Pyramid is one of the few land fragments that rises above the water, offering a rare glimpse of a landmass that nearly vanished.

The tree lobster's long shadow: extinction feared, life found again

The Dryocochelus australis, known as the Lord Howe Island stick insect or tree lobster, was long believed extinct since 1920. Its decline began after 1918, when a ship wreck near Lord Howe allowed rats to reach land and prey on the insects. In 1960, a few tree lobsters were found on Ball's Pyramid, but they were dried remains, not living individuals. Then, in 2001, 20–30 living insects were discovered on Ball's Pyramid—a miraculous sign that life can endure in the most unlikely places. They feed on Melaleuca howeana, the tea-tree endemic to the Lord Howe group, whose presence shaped the insect's survival by providing leaves to eat. This intertwined life—one rock in the sea and one stubborn species—reminds us that even a single stone can shelter life and illuminate a submerged chapter of Earth's history.