Back to Buttons as Car Touchscreens Prove More Dangerous Than Texting Behind the Wheel

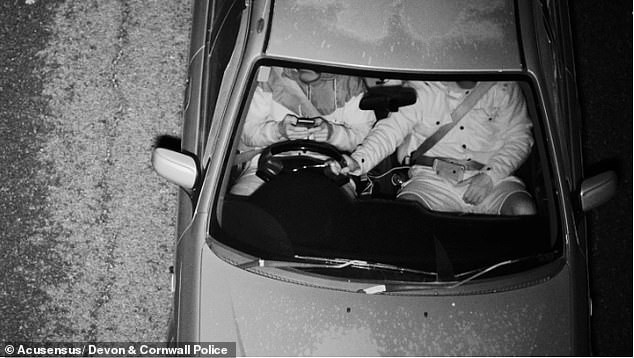

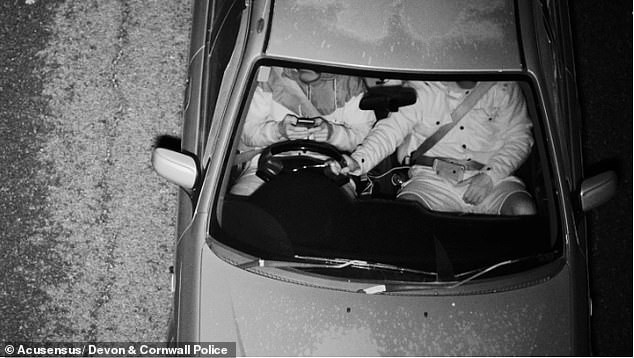

A fancy touchscreen in your new car might seem like the height of luxury, but experts warn it could be putting you in serious danger. Tapping on your in‑car entertainment system to change the music or adjust the heating can be even more risky than using your phone at the wheel. Studies show that drivers' reaction times worsen by over 50 per cent while fiddling with a touchscreen interface. That is an even bigger impact on safety than texting or taking a call on your mobile, which increase the time to react by 35 per cent and 46 per cent respectively. Now there is a growing call from experts to ditch the unnecessary tech and return to a traditional dashboard with physical buttons. The issue is that touchscreen interfaces require drivers to look away from the road for unacceptably long periods of time to control basic functions. While that might be fine for features like reversing cameras and navigation, this becomes a real problem when you need to click through a menu to turn on the windscreen wipers.

In This Article:

- Touchscreens trigger visual, manual and cognitive distraction all at once

- TRL study shows longer stopping distances and greater distraction on motorways

- Muscle memory over muscle misery why physical controls feel safer

- ANCAP calls for a return to buttons as safety pushback grows

- Safety barriers explained how they work and why they matter

- CatClaw a tiny orange device with a bold idea

- Conclusion the button debate continues and the path forward remains contested

Touchscreens trigger visual, manual and cognitive distraction all at once

Distraction from touchscreen interfaces is often described in three categories: visual, manual, and cognitive. Dr Milad Haghani, a safety expert from the University of Melbourne, told the Daily Mail: 'This is the dangerous combination and a recipe for significant levels of distraction.' Scientists say that the touchscreen interface in your car might be just as dangerous as texting while driving, as experts call for a return to traditional manual buttons.

TRL study shows longer stopping distances and greater distraction on motorways

TRL, an independent transport company, conducted a 2020 study in which drivers were placed on simulated motorways while performing common in‑car tasks. One group used a touchscreen system, such as Apple CarPlay and Android Auto, while the others used an audio‑controlled option. The researchers found that the drivers using touch screens had markedly increased reaction times compared with the baseline or audio‑control group. At motorway speeds, these differences would have meant the drivers travelled several extra car lengths before stopping. Lane keeping and overall driving performance also declined as the drivers used their touchscreens. In some cases, these differences were just as significant, if not larger, than the impacts of texting while driving.

Muscle memory over muscle misery why physical controls feel safer

Manual buttons, on the other hand, are significantly less distracting because they are easier to operate by muscle memory without looking away from the road. Dr Haghani says: 'They only demand the manual distraction element, they take your hand off the wheel, but they let you keep an eye on the road, and they don't require a long and sustained glance duration.' He adds: 'Drivers can quickly learn the muscle memory that is required to interact with those buttons and knobs and then they can manipulate them and execute the tasks by relying solely on that muscle memory and haptic feedback. Screens deprive the driver of that useful muscle memory use.'

ANCAP calls for a return to buttons as safety pushback grows

In Australia and New Zealand, the car safety assessment program ANCAP Safety has announced that it will ask manufacturers to 'bring back buttons' from 2026. While Dr Haghani says that screens are still useful for features that don't need adjusting during the drive, such as navigation, essential features must have physical buttons. 'At least drivers must have the option to access them via easily manipulated buttons or knobs, even if they are included in touchscreen functions too - drivers must be given options,' says Dr Haghani. Tesla has been approached for comment.

Safety barriers explained how they work and why they matter

Road safety authorities describe three main types of safety barriers used to keep vehicles away from hazards. Flexible barriers are made from wire rope supported between frangible posts and can absorb impact but must be repaired after a collision. Semi‑rigid barriers are usually built from steel beams or rails, deflect less than flexible barriers and can be placed closer to hazards when space is tight. Rigid barriers are typically concrete, do not deflect, and are used where there is no room for deflection of other barrier types, such as high‑volume roadwork sites protecting workers and road users.

CatClaw a tiny orange device with a bold idea

A new, innovative mechanism to prevent cars driving onto pavements has been designed by Yannick Read from the Environmental Transport Association (ETA). His prototype, called CatClaw, is the size of a small orange and is designed to be installed in thousands along kerbs and pavements. When a car drives over a CatClaw, its weight pushes a button down, exposing a sharp steel tube that quickly punctures the tyre. While the device is only at the prototype phase, Mr Read says it may one day prevent terror attacks involving cars.

Conclusion the button debate continues and the path forward remains contested

The question of whether to keep screens or return to physical controls is not simple. Proponents of touchscreen interfaces point to convenience and functionality, while safety experts warn of distraction and urge a balanced approach that preserves physical buttons for essential tasks. The debate is ongoing, and manufacturers, regulators, and drivers alike are watching closely.