Babies Could Be Born Without a Biological Mother: Scientists Grow Egg-Like Cells From Skin

In a striking breakthrough, researchers at Oregon Health & Science University have created fertilizable eggs from human skin cells for the first time. This could enable DNA from a man’s skin cell to be placed inside a donor egg and fertilised by another man, potentially producing a baby with no DNA from a woman. The discovery offers two possible paths: it could allow two men to have a child, and it could help women whose eggs are damaged or depleted by disease or treatment to have their own genetic children. Experts describe the advance as major, but safety and ethical questions must be addressed before any clinical trials can go ahead.

In This Article:

Mitomeiosis: How Skin Cells Are Turned Into Egg-Like Cells

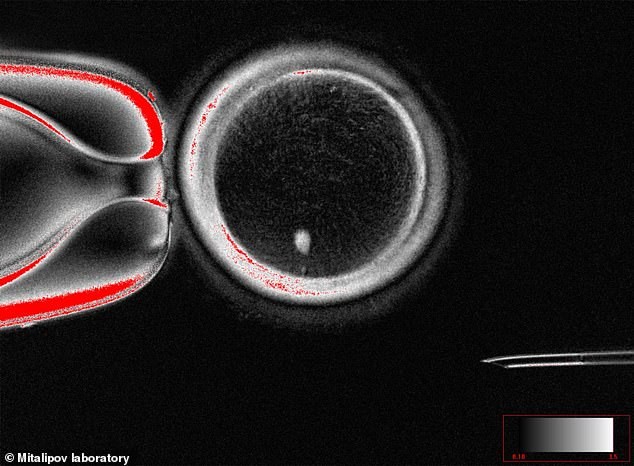

Researchers used somatic cell transfer, transplanting the nucleus from a patient’s skin cell into a donor egg cell with its nucleus removed. Normally eggs carry 23 chromosomes, but skin-derived cells carry 46. Without intervention, this would give the resulting egg an extra chromosome set, which would be problematic for fertilisation. The team solved this with a process they call 'mitomeiosis', which mimics natural cell division and causes one set of chromosomes to be discarded, yielding a functional egg-like cell. In tests, they produced 82 functional eggs using mitomeiosis, and fertilised them in the lab. About nine percent progressed to the blastocyst stage, though the scientists did not culture the blastocysts beyond that point, as in IVF transfers.

Why This Matters for Families and Fertility

Professor Richard Anderson, Deputy Director of the MRC Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, said: 'The ability to generate new eggs would be a major advance. This study shows that the genetic material from skin cells can be used to generate an egg–like cell with the right number of chromosomes to be fertilised and develop into an early embryo. There will be very important safety concerns but this study is a step towards helping many women have their own genetic children.' Experts also note the future possibilities, including scenarios where two men could have a child with genetic material from both, without a woman's DNA.

Limits, Risks and the Road Ahead

Despite the promise, the results come with significant caveats. Approximately 91% of attempted fertilisations did not progress beyond fertilisation, and several of the resulting blastocysts showed chromosomal abnormalities. The work is still at the laboratory stage, and safety and ethical questions must be resolved before any human trials. Nevertheless, experts have called the research an exciting proof of concept. Professor Ying Cheong of the University of Southampton said: 'This breakthrough, called mitomeiosis, is an exciting proof of concept. In practice, clinicians are seeing more and more people who cannot use their own eggs, often because of age or medical conditions. While this is still very early laboratory work, in the future it could transform how we understand infertility and miscarriage, and perhaps one day open the door to creating egg– or sperm–like cells for those who have no other options.'

IVF Today: Context, Costs and Chances

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a medical procedure in which a fertilised egg is implanted into a woman's womb. It is used when natural conception is not possible, and eggs and sperm are combined in a lab before the embryo is transferred. NICE guidelines recommend IVF on the NHS for women under 43 who have tried to conceive for two years. Private IVF is also available, costing around £3,348 per cycle on average (2018 data), with no guarantee of success. The NHS reports that success rates vary by age: about 29% for women under 35; 23% for 35–37; 15% for 38–39; 9% for 40–42; 3% for 43–44; and 2% for 44 and older. Since IVF's first birth in 1978, around eight million babies have been born through the technique. This new line of research could one day alter the infertility landscape, but it remains at an early stage and not ready for clinical use.