A Mouse Gave Birth After Spaceflight and It Could Redefine Humanity's Future

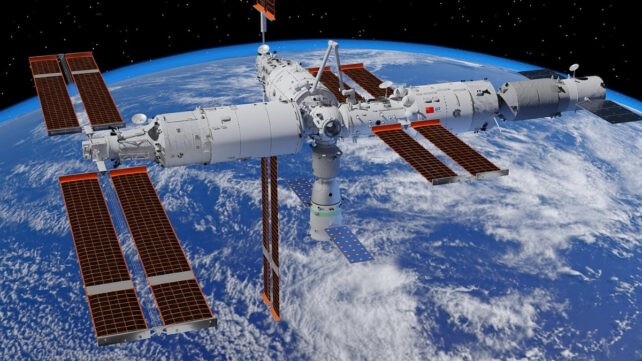

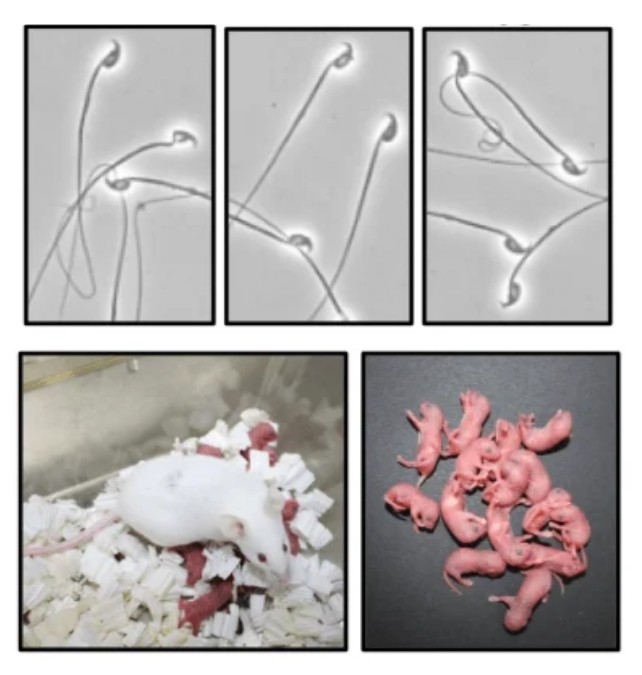

Four mice were launched to space aboard Shenzhou-21, and only one returned to Earth as a mother. On 31 October, China sent four mice numbered 6, 98, 154, and 186 to the country’s space station, roughly 400 kilometers above Earth. They spent two weeks in microgravity, exposed to space radiation and the peculiar conditions of orbital life, before returning safely on 14 November. Then, on 10 December, one of the females gave birth to nine healthy pups. This simple fact might matter more for humanity's future beyond Earth than you might think. In a previous study, sperm from mice that had been in space had been used to fertilize female mice back on Earth. In this new experiment, six of the offspring survived, which researchers consider a normal survival rate. The mother is nursing properly, and the pups are active and developing well. Wang Hongmei, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Zoology, emphasized the significance of their discovery that short-term spaceflight didn't damage the mouse's ability to reproduce. This wasn't just about sending mice to space for the sake of it. Mice share high genetic similarity with humans, reproduce quickly, and respond to physiological stresses in ways that often mirror human biology. If space breaks something fundamental about mammalian reproduction, it would show in mice first. The mission wasn't smooth sailing, though. When the return schedule for Shenzhou-20 changed unexpectedly, the mice faced an extended stay and potential food shortage. The ground team scrambled, testing emergency rations from the astronauts' own supplies, including compressed biscuits, corn, hazelnuts, and soy milk. After verification tests on Earth, soy milk won out as the safest emergency food. Water was pumped into the habitat through an external port while an AI monitoring system tracked the mice's movements, eating patterns, and sleep cycles in real time, helping predict when supplies would run out. Throughout their orbital stay, the mice lived under carefully controlled conditions. Lights turned on at 07:00 and off at 19:00 to maintain an Earth-based circadian rhythm. Their food was nutritionally balanced but intentionally hard, satisfying their need to grind their teeth. Directional airflow kept the habitat clean by blowing hair and waste into collection containers. Now researchers will monitor these space pups closely, tracking their growth curves and checking for physiological changes that might hint at hidden effects from their mother's space exposure. They'll also test whether these offspring can reproduce normally themselves, searching for multi-generational impacts. The ultimate goal extends beyond mice. Before humans attempt years-long missions to Mars or establish permanent settlements on the Moon, scientists need to know whether reproduction works normally in space or after space exposure. Can mammals conceive, gestate, and give birth in reduced gravity? Do cosmic rays damage eggs or sperm in ways that only appear in the next generation? One mouse giving birth doesn't answer all those questions. But it's a promising start. This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.

Short-term spaceflight did not damage the mouse's ability to reproduce

Four mice—6, 98, 154, and 186—were launched to space aboard Shenzhou-21. After a two-week stay in microgravity, they returned to Earth on 14 November. On 10 December, one female gave birth to nine healthy pups. In this experiment, six of the offspring survived, which researchers consider a normal survival rate. The mother is nursing properly, and the pups are active and developing well. Wang Hongmei, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Zoology, emphasized the significance of discovering that short-term spaceflight did not damage the mouse's ability to reproduce. The mission faced a setback when the return schedule for Shenzhou-20 changed unexpectedly, extending the stay and threatening food supplies. The ground team scrambled to test emergency rations from the astronauts' supplies, including compressed biscuits, corn, hazelnuts, and soy milk, with soy milk ultimately chosen as the safest option. Water was pumped into the habitat via an external port while an AI monitoring system tracked the mice's movements, eating patterns, and sleep cycles in real time, helping predict when supplies would run out. During their orbital stay, the mice lived under carefully controlled conditions. Lights were set to 07:00–19:00 to maintain an Earth-based circadian rhythm. Their food was nutritionally balanced but intentionally hard to satisfy their need to grind their teeth. Directional airflow kept the habitat clean by blowing hair and waste into collection containers. Researchers will monitor these space pups closely, tracking growth curves and checking for physiological changes that might hint at hidden effects from their mother's space exposure. They will also test whether these offspring can reproduce normally themselves, searching for multi-generational impacts. The goal is not only to understand mice but to inform human exploration. Before humans attempt years-long missions to Mars or establish lunar settlements, scientists need to know whether reproduction works normally in space or after space exposure. This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.

Implications for humanity's future beyond Earth

Mice share a high degree of genetic similarity with humans, reproduce quickly, and respond to physiological stresses in ways that often mirror human biology. If space were to disrupt a fundamental aspect of mammalian reproduction, the earliest signs would likely appear in mice. This first birth after spaceflight is therefore an important signal, but not a conclusion. Researchers stress that many questions remain. Can mammals conceive, gestate, and give birth in reduced gravity? Do cosmic rays damage eggs or sperm in ways that only show up in the next generation? What long-term or multi-generational effects might appear after years of exposure or exposure across generations? One birth does not answer all of these questions, but it provides a crucial data point as scientists build a plan for long-duration missions—whether to Mars or to establish lunar habitats. The scientists will continue monitoring the space pups, tracking their growth curves and looking for physiological changes that might hint at hidden effects from their mother's space exposure. They will also test whether the offspring can reproduce normally themselves, to assess any potential multi-generational impacts. If the science supports it, future experiments could proceed to multi-generational studies to understand how space exposure affects mammalian reproduction over time. The ultimate objective remains clear: ensure that humans can conceive, gestate, and birth safely in space or in habitats off Earth before committing to long missions. This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.